|

1/18/2019 3 Comments The Second Week

From January 9th to January 15th, our courtwatchers observed 193 individual people facing charges across three divisions of Boston Municipal Court (BMC Central, Roxbury, and Dorchester).[1] Some of these people had multiple open cases. Courtwatchers observed 198 cases in which they documented a specific outcome.

This week, roughly half of the cases observed (49.49%) involved only charges that Suffolk County District Attorney Rachael Rollins has pledged to decline to prosecute, either by dismissing at arraignment or diverting through a non-criminal proceeding, program, or outcome. Again, that means half of the cases we observed processed by our criminal courts this week represented crimes that District Attorney Rollins has identified as low-level, non-violent crimes rooted in poverty, mental illness, and addiction. Our digest will focus on the data courtwatchers collected about cases that exclusively involved charges from DA Rollins’ Decline to Prosecute list.[2]

There were 98 cases involving ONLY charges on the decline to prosecute list.

In cases of conditional dismissals, individuals were frequently required to report back to court on a future date to prove compliance with the condition—even when that compliance took the form of payment of a fee to the court itself, which the court should be able to verify on its own. When people are required to appear in court, it may mean they have to take time off work, school, or parenting, or pay for transportation to make it there which can be a challenge for working class families.

*A note on terms: the distinction between diversion and conditional dismissal is a gray area. In her campaign, Rachael Rollins used both terms. We ask courtwatchers to try to distinguish between the two and report their categorizations based on what they observe and hear in court, but it may be a distinction without a difference. We’re trying to decipher what the administration considers the difference based on what terms are being used in court by prosecutors.*

What gets dismissed?

Just as we saw last week, the vast majority of dismissals were driving cases – 41 of the 51 cases (80%) that were dismissed. The other 10 cases dismissed at arraignment were incidents of: Trespass (4); Disorderly Conduct (1); Drug Possession (3); and Shoplifting (2).

A substantial majority of driving cases were dismissed this week at arraignment.

What gets diverted?

Release or Detention Decisions

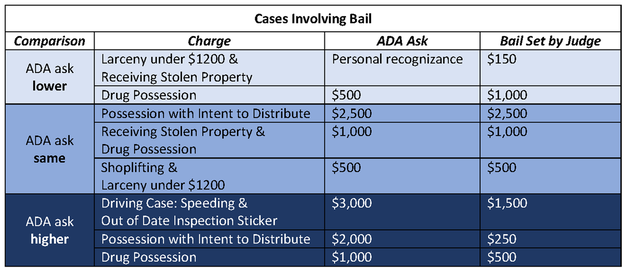

ADAs’ bail recommendations are incredibly influential because they set the tone of the conversation about the case. Judges ask ADAs to make their bail recommendation first, before the defense attorney has the opportunity to speak. ADAs often asked for bails equal to or higher than the judge ultimately imposed. Again, ADAs get to direct the conversation on bail, so a judge’s decision to set bail at all and to set a specific amount is significantly informed by the ADA.

In two of the cases where the judge didn’t flatly adopt the ADA’s recommendation, the judge set exactly half the bail amount the ADA requested. This is significant because it suggests the judge simply split the difference between release on personal recognizance requested by the defense and the ADA bail recommendation. Bail should be tailored to getting someone to return to court and, by law, must factor in the person’s ability to pay. It should not be a knee-jerk compromise.

In the remaining 7 cases, we don’t know the release decision or case outcome because the courtwatcher left before the judge resumed hearing the case, the arraignment was continued, or the person being arraigned remained detained (in one case despite the judge deciding to release them on personal recognizance on the pending trespass & drug possession charges) in order to resolve a warrant in another court. The charge breakdowns are as follows [keep in mind that some folks had multiple charges]:

In 18 of these cases, the person being arraigned was in jail at the time of arraignment. Among those 18 individuals,

In other words, 11 people spent time in jail and ultimately were not prosecuted or were released; they were detained without an ability to shower, change clothes, see their kids, walk their pets, take their medications, or communicate with their jobs or families—only to have a judge determine there was no good reason to detain them.

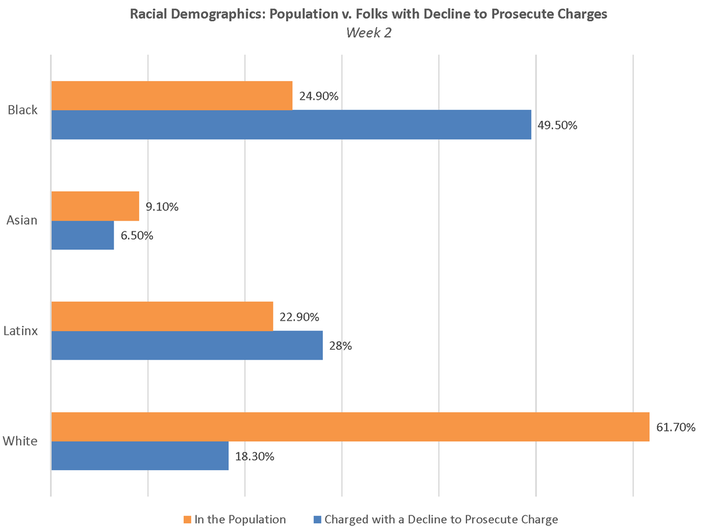

Black and Latinx defendants are once again starkly overrepresented compared to the population, while white defendants are starkly underrepresented.

Whose cases get dismissed or diverted?

We wondered about the racial breakdown of dismissals and diversion as compared to the entire group of cases involving only charges to be declined. Basically, if you're white, are you more likely to have your case get dismissed or diverted?

In fact, the racial demographic breakdowns are remarkably similar, and the percentage of white folks whose cases get dismissed/diverted is lower than the whole decline to prosecute dataset, meaning comparatively fewer white folks are having their cases dismissed or diverted. Decline to Prosecute Racial Demographics: Week 2 49.5% Black, 28% Latinx; 18.3% white; 5.4% East Asian; and 1.1% South Asian. Dismissed/Diverted Racial Demographics: Week 2 50% Black; 30.4% Latinx; 12.5% white; 5.3% East Asian; and 1.8% South Asian. However, this finding does not suggest that ADAs are showing special leniency to non-white individuals. The vast majority of cases which get dismissed or diverted are driving cases. These kinds of offenses are disparately enforced from the outset, by police. We suspect white folks are not being stopped by police as often, and certainly not arrested as often, for driving offenses, and that’s where the underlying disparity exists. A substantial body of research – from academic studies to opinions by our own Supreme Judicial Court – confirms that white people are not arrested nearly as often for minor crimes and driving offenses in Boston, in Massachusetts, and in the U.S. in its entirety.[4] Beyond the Charges to Be Declined: Other Charges

As a point of interest, we emphasize that a significant number of the “other” cases also exclusively involved minor matters. For example, 12 of the 100 cases reflecting charges not on the declination list were for jurors who failed to appear for jury duty—most of them because they thought they were ineligible. An additional 11 of these 100 cases involved some kind of default removal – for example, missed court dates or failure to prove completion of community service. Many of those defaults were cleared and almost all of the jury cases were dismissed prior to arraignment.

Cause for Concern: Practices to Change

As stated above, 41 cases involving only charges to be declined were not dismissed or diverted. Those cases should also be declined, and we hope this will change in the weeks to come.

Courtwatchers observed 1 declination case involving a charge of Wanton/Malicious Destruction of Property in which an ADA asked for $500 bail but the judge ultimately released the individual on personal recognizance. In the 8 declination cases in which an ADA requested bail this week, the judge imposed bail 7 out of those 8 times—a rate of 87.5%. ADAs have a tremendous amount of influence over bail. We again emphasize that ADAs should always recommend release on personal recognizance in cases when the person is not a flight risk and should never request bail for charges that are on the do not prosecute list. Takeaways: Reactions from the CourtWatch MA team

We appreciate that District Attorney Rollins continues to give interviews focused on the importance of declining the 15 crimes she has identified as criminalizing poverty, addiction, and mental illness.

But as this week’s findings again demonstrate, her office is still actively prosecuting people for these crimes. In many cases, even if the charge is dismissed at arraignment that dismissal comes with conditions, whether court costs or community service hours. We have concerns about these conditions. While we support DA Rollins’ pledge to not criminally prosecute people for being poor or suffering from addiction or mental illness, in many cases these folks are similarly burdened by court conditions, whether a fine/fee or community service. As traditionally implemented by our court system, community service is highly prescribed manual labor. Even when a person is given the option to serve at a nonprofit of their choosing, community service may be difficult to complete if that person works, has kids, or doesn't have a car. Finally, judges and ADAs alike have misconceptions about what it means to require someone to complete community service hours through the state program. We look forward to a public release of office policy that will give Assistant District Attorneys guidance on how to carry out DA Rollins’ vision.

[1] This count may include a handful of status hearings, restraining orders, or other types of hearings that were not initial arraignments. By our best estimation based on the data we collected, this week’s observed cases involved 207 unique dockets. However, courtwatchers did not always record disposition by individual docket, more often noting the hearing outcome by defendant even when they wrote down multiple docket numbers. Further, we note that the total number of hearings observed is not the total number of arraignments which transpired in those courts. For a full count of arraignments, you can view sparse information about all criminal cases, by court and date of filing, at masscourts.org. Select the court, use the “case type” tab, select the relevant date(s), and select both “criminal” and “criminal cross site” as the case type.

[2] Because of limited capacity of the CourtWatch MA team, we have not verified every case against the limited available charge information on masscourts.org. We have verified the charge in any case where the courtwatcher left the charge blank (roughly 15 cases out of 198), indicated they did not hear the charge, or noted that reading the charge was waived in court. It is of course possible courtwatchers misheard the charge(s) in any given case; our data collection is not a substitute for open government and we are very hopeful that District Attorney Rollins will release data tracked by the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office with some regularity going forward. [3] Courtwatchers write down demographic information (age, race, gender) based on observation alone; we recognize that this is an imperfect way to determine markers of identity. We ask courtwatchers to note this information because (1) courts are unlikely to disclose this information even if we requested every docket; and (2) the system operates based on an individual’s outward perception and expression, regardless of their stated identity, so demographic observations are a reasonable methodology for this particular project. [4] Commonwealth v. Warren, 475 Mass. 530, 539–40 (2016); Jeffrey Fagan et al., Final Report, An Analysis of Race and Ethnicity Patterns in Boston Police Department and Field Interrogation, Observation, Frisk, and/or Search Reports 2 (June 15, 2015); ACLU of Massachusetts, Black, Brown and Targeted (2014); Amy Farrell, et al. Massachusetts Racial and Gender Profiling Study, 24-27 (2004). Based on 2011 data, the Bureau of Justice Statistics found that Black drivers are more likely to be stopped, ticketed, and searched than white drivers, and more often for violations other than speeding, like a vehicle defect or a record check. See also generally Emma Pierson, et al., A Large-Scale Analysis of Racial Disparities in Police Stops Across the United States, 5-7, Stanford University (2017); David A. Harris, ACLU, Driving While Black: Racial Profiling on Our Nation’s Highways (1999). To differing degrees, this pattern of stopping and arresting people of color for “driving while Black” or “driving while Latinx” emerges around the country, from Philadelphia to Milwaukee to Illinois.

3 Comments

1/22/2019 06:38:01 am

I love this analysis but I think they got one stat wrong - they should not compare share of dismissals to share of population. They should compare to share of prosecutions. When you make that comparison, white are no longer less likely to get a dismissal. And then, when you observe that the whites are being dismissed at the same rate, but for more serious offenses, you in fact see they are at an advantage.

Reply

CourtWatch MA

1/22/2019 07:09:02 am

Thanks for your feedback! Always great to have input dissecting and understanding the numbers.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorCourt Watch MA is a community project with the goal of shifting the power dynamics in our courtrooms by exposing the decisions judges and prosecutors make about neighbors every day. Archives

November 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed