|

1/30/2019 0 Comments The Third Week

From January 16th to January 22nd, our courtwatchers observed 161 people facing charges at arraignment across three divisions of Boston Municipal Court (BMC Central, Roxbury, and Dorchester).[1]

This week, slightly more than half of the cases observed (50.9%) involved only charges that Suffolk County District Attorney Rachael Rollins has pledged to decline to prosecute, either by dismissing at arraignment or diverting through a non-criminal proceeding, program, or outcome. Again, that means half of the cases we observed this week represented crimes that District Attorney Rollins has identified as low-level, non-violent crimes rooted in poverty, mental illness, and addiction. We want to mention up front that 34.7% of all 161 cases observed this week were driving charges. In other words, 35% of criminal dockets this week in these BMC courts were essentially aggravated traffic court—judges overseeing, and often diverting or dismissing, driving offenses for which folks are still frequently arrested and occasionally held in jail. This concerns us. We hope lawmakers take note. Our digest again focuses on the data courtwatchers collected about cases that exclusively involved charges from DA Rollins’ Decline to Prosecute list.[2] An Updated Note on Terms

As we mentioned last week, we are unsure of the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office distinction between diversion and dismissal. In her campaign, Rachael Rollins used both terms. We have asked courtwatchers to try to report case categorizations based on what they observe and hear in court. But, as one of our courtwatchers said this week, “This is confusing - diverted versus dismissed. I never heard ‘diverted’ this a.m. in BMC but I heard lots of ‘dismissed’ with the condition of 4 hours community service.”

From this point forward we are only going to categorize cases that are dismissed outright as dismissals. Cases that are conditionally dismissed – with court costs, community service hours, or a treatment program – and therefore require a subsequent appearance in court will be considered diverted cases. We think this is both more accurate and more useful coding. As addressed in detail below, we are concerned about the impact that imposing conditions which require time, money, or transportation will have on poor and working class people facing charges.

There were 82 cases involving ONLY charges on the decline to prosecute list this week.

When a person pays a fee to the court or serves community service through the state program administered by the probation department, the court should be able to verify compliance with that condition on its own. Instead, our courts insist that people appear in court again, not only requiring them to take time off work, school, or parenting, or pay for transportation to make it there, but also potentially setting up a new cycle of criminal appearances if for some reason they are unable to appear in court that day. If a person “fails to appear” in court, that becomes a default on their record. A default on your record can easily become an open warrant; indeed, courtwatchers saw that happen four (4) times this week. Imagine being arrested and held in jail for a weekend because of a $100 fee the system thinks is unpaid (whether or not you already paid it) because you were in the hospital and therefore missed your last court date to prove compliance. Any new open warrant is just a drop in the bucket among the 390,000 open warrants in Massachusetts, but one that can have devastating consequences and can lead to debt-based jail time for the people caught up. What gets dismissed?

|

|

|

Driving Charges (56 total)

|

|

|

Dismissed (without conditions)

|

28

|

50%

|

|

Diverted (with conditions)

|

15

|

26.8%

|

|

Released on Personal Recognizance

|

5

|

8.9%

|

|

Other Outcome

(bail set, arraignment continued, held for transport, warrant issued, not resolved before courtwatcher left) |

8

|

14.3%

|

What gets diverted?

As stated above, this week we categorized any dismissal that included conditions requiring a future court appearance as a diverted case in an effort to more accurately represent the data we collect.

Much like dismissals, the vast majority of diversions were driving cases – 15 of the 18 (83.3%) cases diverted this week. For driving cases, judges usually gave the person an option of returning with proof of license/registration/insurance, paying a fee between $50 and $150, or completing 4 to 12 hours of community service. The precise outcome depended on the judge.

The other diverted cases were:

Much like dismissals, the vast majority of diversions were driving cases – 15 of the 18 (83.3%) cases diverted this week. For driving cases, judges usually gave the person an option of returning with proof of license/registration/insurance, paying a fee between $50 and $150, or completing 4 to 12 hours of community service. The precise outcome depended on the judge.

The other diverted cases were:

|

|

Diverted Cases

(18 total: 15 driving charges, 3 other) |

|

|

Charge(s)

|

Type of Diversion

|

Outcome

|

|

Trespass & Disorderly Conduct

|

Community Service

|

4 hours

|

|

Threat to Commit a Crime

|

Mental Health

|

Competency evaluation

|

|

Shoplifting

|

Community Service

|

4 hours

|

Release or Detention Decisions

In 15 cases that advanced as criminal matters, the person being arraigned was released on personal recognizance. In many such cases, the court also imposed conditions—especially common was a stay away or no contact order for the place of the incident or a person involved.

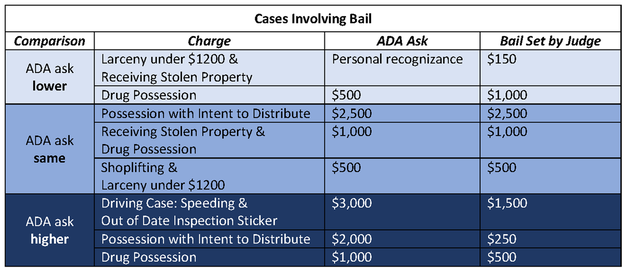

There were 3 cases this week, all involving drug possession, in which an ADA asked for bail but the judge released the individual on personal recognizance. Once again, we see that ADAs often asked for bails equal to or higher than what the judge ultimately imposed. We are not sure whether DA Rollins has given her ADAs a clear directive on not seeking bail for these 15 charges; as points of comparison, Wesley Bell in St. Louis County had day-one interim policy, whereas DA Larry Krasner in Philadelphia released his bail policy in an internal memo dated February 15th, about six weeks into his term.

There were 3 cases this week, all involving drug possession, in which an ADA asked for bail but the judge released the individual on personal recognizance. Once again, we see that ADAs often asked for bails equal to or higher than what the judge ultimately imposed. We are not sure whether DA Rollins has given her ADAs a clear directive on not seeking bail for these 15 charges; as points of comparison, Wesley Bell in St. Louis County had day-one interim policy, whereas DA Larry Krasner in Philadelphia released his bail policy in an internal memo dated February 15th, about six weeks into his term.

Here are the stories of those 3 cases:

- The man being arraigned was a passenger in a vehicle that was pulled over for broken tail lights and plate lights. Police ran a check on his ID and found an open warrant, then searched him and found 11 rock-like substances believed to be crack cocaine. The search did not reveal additional drug paraphernalia on his person. He admitted to being a drug user and is being charged with Class B possession with intent to distribute. As a reminder, intent to distribute is a judgment call the ADA makes and is not based on a weight limit. The ADA asked for $500 cash bail and transport to BMC Central for a warrant recall, noting that he had multiple defaults. The defense noted that he was not employed and would be unable to afford bail. Also, the probation warrant was the result of him voluntarily contacting probation himself to inform them of his release from a program. The judge did not set bail, releasing the man on personal recognizance, and scheduled a probable cause hearing for March.

- In another case where a man was charged with Class B drug possession, the ADA asked for bail to be revoked on another case, $300 bail to be set on the possession charge, and that the man be required to abstain from alcohol. The judge released the man on personal recognizance with the condition of alcohol abstention.

- In a third case where a man was charged with both drug possession and possession with intent to distribute, the ADA asked for a stay away order and $1500 bail. The judge released him on personal recognizance with an order to stay away from his codefendant. This man’s codefendant was arraigned on more serious charges, including possession of a stolen, loaded gun. For him, the ADA asked for and the judge set $25,000 bail, a GPS, a stay away order, and a curfew—despite his defense attorney advocating for release given his strong ties to the community. As a reminder, bail is only supposed to ensure one’s appearance in court and judges are required to consider a person’s ability to pay, regardless of the seriousness of the alleged crime.

In the remaining 15 cases, we don’t know the final release decision or case outcome because the arraignment was continued—i.e. postponed to a future date or time (6 cases), the person being arraigned remained detained (despite the judge deciding to release them on personal recognizance on the pending charges) in order to resolve a warrant in another court (3 cases), the person failed to appear for arraignment and a warrant was issued for their arrest (4 cases), or the courtwatcher left before the disposition was announced (2 cases).

The charge breakdowns are as follows [keep in mind that some folks had multiple charges]:

|

Charge

|

Number of Cases

|

|

Trespass

|

8

|

|

Shoplifting

|

2

|

|

Larceny under $1200

|

1

|

|

Disorderly Conduct

|

3

|

|

Disturbing the Peace

|

(zero)

|

|

Receiving Stolen Property

|

3

|

|

Driving Cases (suspended or revoked license or registration)

|

56

|

|

Breaking and entering for the purpose of shelter

|

(zero)

|

|

Wanton/Malicious Destruction of Property

|

(zero)

|

|

Threats (not domestic violence related)

|

3

|

|

Minor in Possession of Alcohol

|

(zero)

|

|

Drug Possession

|

9

|

|

Drug Possession with Intent to Distribute

|

5

|

|

Resisting Arrest

|

2

|

In 16 of these cases, the person being arraigned was in jail at the time of arraignment. Among those 16 individuals,

In other words, 12 people spent time in jail and ultimately were not prosecuted or were released; they were detained without an ability to shower, change clothes, see their kids, walk their pets, take their medications, or communicate with their jobs or families—only to have a judge determine there was no good reason to detain them.

Further, this means in 75% of cases in which a bail magistrate declined to release someone, the judge released the individual or diverted or dismissed that person’s case.

- 8 were released on personal recognizance,

- 1 had their case diverted (charges were trespass & disorderly conduct), and

- 3 had their cases dismissed (charges were trespass & disorderly conduct; trespass & resisting arrest; a driving charge).

In other words, 12 people spent time in jail and ultimately were not prosecuted or were released; they were detained without an ability to shower, change clothes, see their kids, walk their pets, take their medications, or communicate with their jobs or families—only to have a judge determine there was no good reason to detain them.

Further, this means in 75% of cases in which a bail magistrate declined to release someone, the judge released the individual or diverted or dismissed that person’s case.

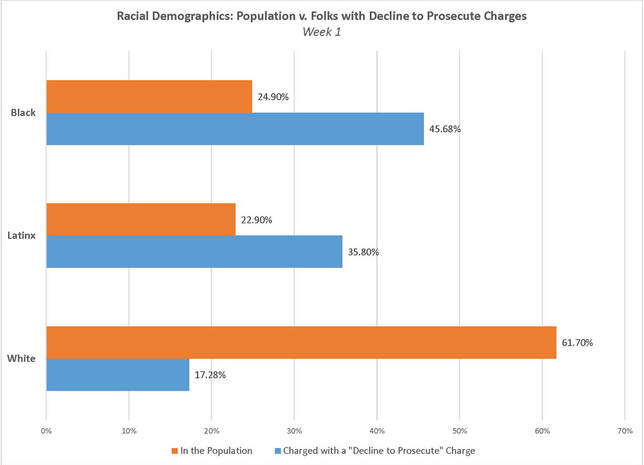

Demographics[3] – Who is Prosecuted for these Offenses?

|

|

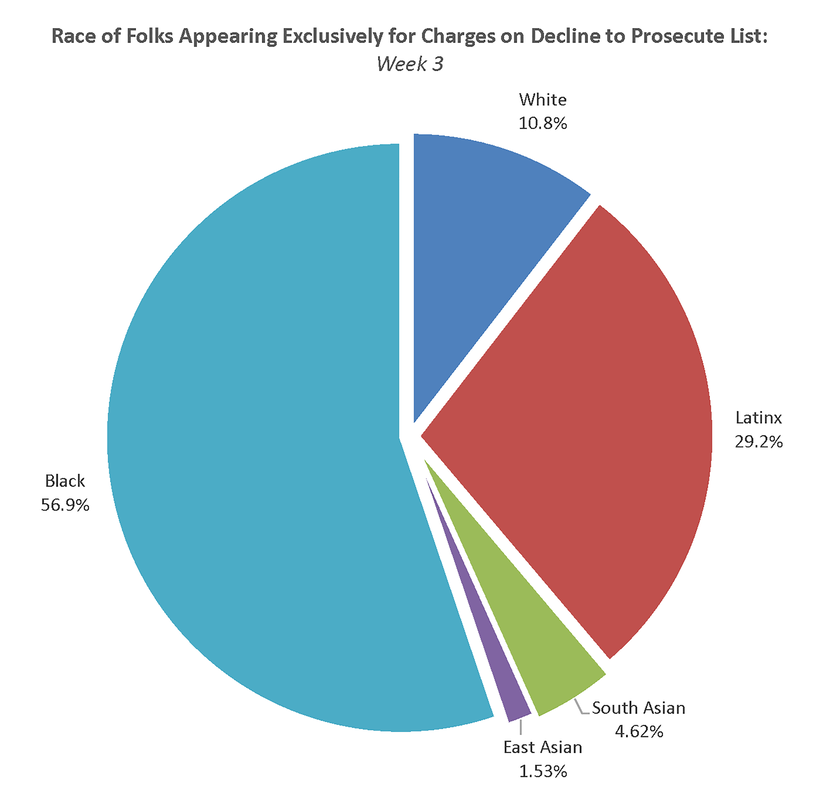

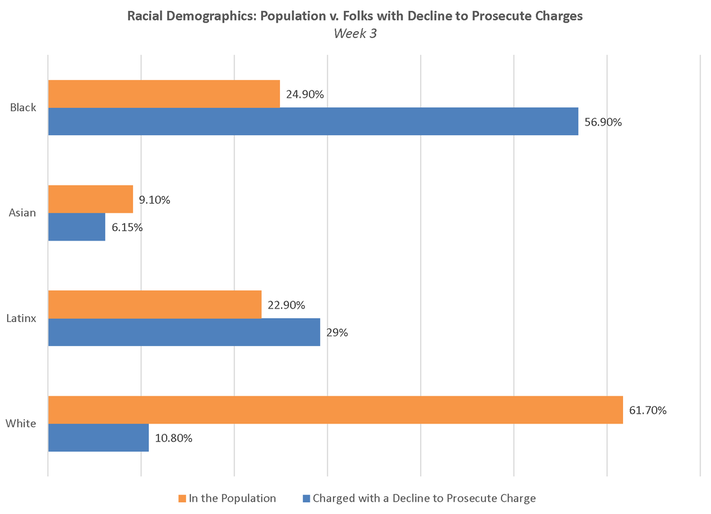

Of the 65 declination cases observed this week in which courtwatchers noted demographic information, the racial breakdown of the people arraigned was as follows:

56.9% Black, 29.2% Latinx; 10.8% white, 4.6% South Asian, and 1.5% East Asian. |

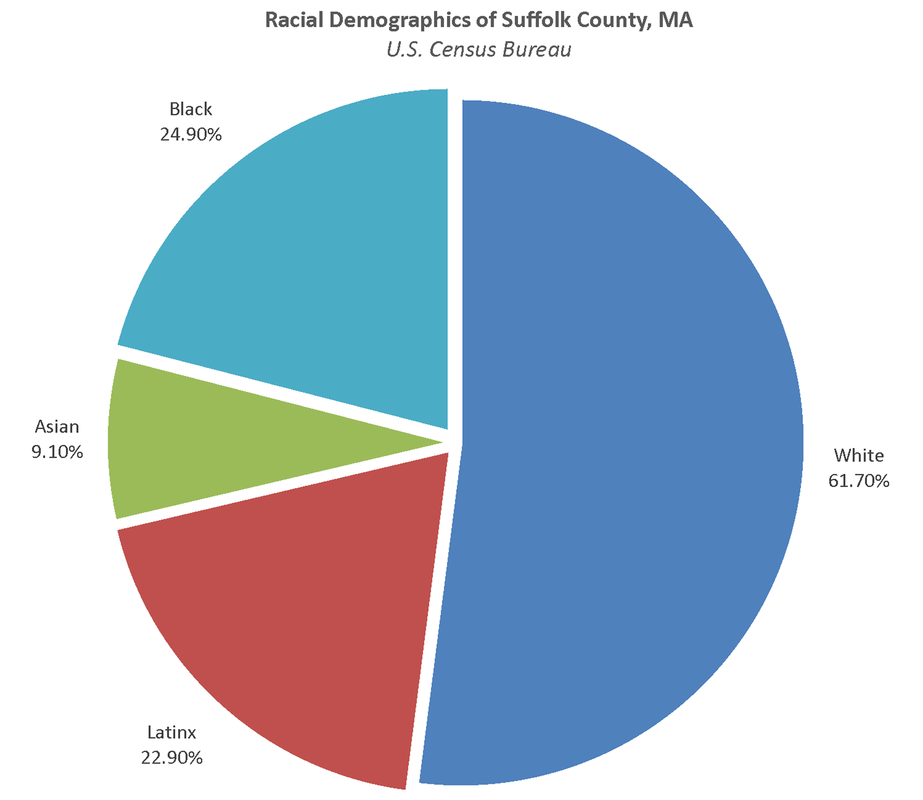

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the demographics of Suffolk County are as follows:

24.9% Black or African American, 22.9% Hispanic of Latino, 61.7% white, 9.1% Asian, 3.4% two or more races, .7% Native American or Alaskan Native, .2% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander |

Black and Latinx defendants are once again starkly overrepresented compared to the population, while white defendants are starkly underrepresented.

Cause for Concern: Practices to Change

As stated above, 31 cases involving only charges to be declined were not dismissed or diverted. Those cases should also be declined, and we expect this to change in the weeks to come.

Courtwatchers observed 3 cases involving charges from the decline to prosecute list in which an ADA asked for bail but the judge ultimately released the individual on personal recognizance. We again emphasize that ADAs should always recommend release on personal recognizance in cases when the person is not a flight risk and should never request bail for charges on the do not prosecute list.

There were also instances this week in which an ADA asked for conditions and the judge overruled the ADA and dismissed the case outright. In all cases, we hope the ADA asks for the least burdensome outcome that will resolve the case. For all 15 charges DA Rollins has identified, we believe the cases should generally be dismissed without any conditions.

We were very concerned this week that so many warrants were issued when a person did not appear in court. In 4 cases ADAs asked for warrants to be issued and the judge obliged. We encourage DA Rollins to train ADAs to scrutinize whether a default reflects a willful failure to appear, or if instead there may be another explanation to excuse a person’s absence from court. We often see people who did not appear in court because of housing insecurity (they never got the summons) or who were unable to appear because of a hospital stay or commitment to a treatment program. Being arrested is a traumatic experience for anyone, and DA Rollins should do what she can to minimize arrests. Overall, failure to appear rates remain incredibly low—and studies show that they can be lowered further by redesigning confusing summons notices and sending text message reminders.

Courtwatchers observed 3 cases involving charges from the decline to prosecute list in which an ADA asked for bail but the judge ultimately released the individual on personal recognizance. We again emphasize that ADAs should always recommend release on personal recognizance in cases when the person is not a flight risk and should never request bail for charges on the do not prosecute list.

There were also instances this week in which an ADA asked for conditions and the judge overruled the ADA and dismissed the case outright. In all cases, we hope the ADA asks for the least burdensome outcome that will resolve the case. For all 15 charges DA Rollins has identified, we believe the cases should generally be dismissed without any conditions.

We were very concerned this week that so many warrants were issued when a person did not appear in court. In 4 cases ADAs asked for warrants to be issued and the judge obliged. We encourage DA Rollins to train ADAs to scrutinize whether a default reflects a willful failure to appear, or if instead there may be another explanation to excuse a person’s absence from court. We often see people who did not appear in court because of housing insecurity (they never got the summons) or who were unable to appear because of a hospital stay or commitment to a treatment program. Being arrested is a traumatic experience for anyone, and DA Rollins should do what she can to minimize arrests. Overall, failure to appear rates remain incredibly low—and studies show that they can be lowered further by redesigning confusing summons notices and sending text message reminders.

Takeaways: Reactions from the CourtWatch MA team

Comparing each week to the week before, we have noticed more cases involving the 15 charges being declined and fewer cases continuing as criminal matters. This is a positive trend line. We hope it is not an anomaly but instead the result of ADAs learning how to apply District Attorney Rollins’ policy to decline the 15 crimes she has identified as criminalizing poverty, addiction, and mental illness.

Still, as this week’s findings again demonstrate, her office is still actively prosecuting people for these crimes. As we see this week from our careful sifting of dismissed and diverted cases, in many cases folks face court costs or community service hours to resolve their cases and are given future court appearances to prove compliance.

We remain deeply concerned about ADAs requesting and judges imposing conditions. DA Rollins recognizes that these 15 offenses criminalize poverty. Forcing someone to pay court costs as a condition before dismissal is counterproductive. If someone can’t make bail – which is refundable – will they be able to pay off court fees? In many cases, the reason for the underlying issue is purely economic. For example, we see so many driving cases in which someone’s license was suspended because of an unpaid fee, whether $6,000 owed to the IRS or outstanding child support. In order to resolve their diverted case, they’ll have to resolve the debt or get on a payment plan as well as pay their court costs and a license reinstatement fee. And if they don’t? A new default, a new warrant, perhaps a weekend in jail.

In cases when it appears the judge is being lenient, poor and working class people may still struggle to meet expensive or time-consuming conditions that have no public safety benefit. We hope DA Rollins will encourage ADAs to think carefully about ability to pay not only when requesting bail—which lawfully can only be imposed to encourage someone to appear in court for future appearances—but also when (1) imposing conditions of dismissal and (2) seeking a default or warrant instead of a continuance that merely postpones and reschedules the arraignment. For example, this week a man was arraigned on charges of trespass & receiving stolen property who also had a default on his record. His attorney explained that he had been in the hospital during that earlier court hearing which caused the default. Nevertheless, he had to pay a $50 fee to remove the default.

Still, as this week’s findings again demonstrate, her office is still actively prosecuting people for these crimes. As we see this week from our careful sifting of dismissed and diverted cases, in many cases folks face court costs or community service hours to resolve their cases and are given future court appearances to prove compliance.

We remain deeply concerned about ADAs requesting and judges imposing conditions. DA Rollins recognizes that these 15 offenses criminalize poverty. Forcing someone to pay court costs as a condition before dismissal is counterproductive. If someone can’t make bail – which is refundable – will they be able to pay off court fees? In many cases, the reason for the underlying issue is purely economic. For example, we see so many driving cases in which someone’s license was suspended because of an unpaid fee, whether $6,000 owed to the IRS or outstanding child support. In order to resolve their diverted case, they’ll have to resolve the debt or get on a payment plan as well as pay their court costs and a license reinstatement fee. And if they don’t? A new default, a new warrant, perhaps a weekend in jail.

In cases when it appears the judge is being lenient, poor and working class people may still struggle to meet expensive or time-consuming conditions that have no public safety benefit. We hope DA Rollins will encourage ADAs to think carefully about ability to pay not only when requesting bail—which lawfully can only be imposed to encourage someone to appear in court for future appearances—but also when (1) imposing conditions of dismissal and (2) seeking a default or warrant instead of a continuance that merely postpones and reschedules the arraignment. For example, this week a man was arraigned on charges of trespass & receiving stolen property who also had a default on his record. His attorney explained that he had been in the hospital during that earlier court hearing which caused the default. Nevertheless, he had to pay a $50 fee to remove the default.

Finally, we look forward to a public release of office policy and SCDAO internal office data.

DA Rollins has been in office for more than 3 weeks. The electorate is concerned and deserves to know what’s happening behind closed doors.

[1] This figure reflects four days of hearings because Monday, January 21st was a court holiday for Martin Luther King, Jr., Day. This week we took special care to remove nine (9) cases from our dataset representing status hearings, restraining orders, or other types of hearings that were not initial arraignments. We again note that the total number of hearings observed is not the total number of arraignments which transpired in those courts. For a full count of arraignments, you can view sparse information about all criminal cases, by court and date of filing, at masscourts.org. Select the court, use the “case type” tab, select the relevant date(s), and select both “criminal” and “criminal cross site” as the case type.

[2] Because of limited capacity of the CourtWatch MA team, we again did not verify every case against the limited available charge information on masscourts.org. We have verified the charge in any case where the courtwatcher left the charge blank, did not hear the charge, or noted that reading the charge was waived in court. It is of course possible courtwatchers misheard the charge(s) in any given case; we reiterate that our data collection is not a substitute for open government and we are very hopeful that District Attorney Rollins will release data tracked by the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office with some regularity going forward.

[3] Courtwatchers write down demographic information (age, race, gender) based on observation alone; we recognize that this is an imperfect way to determine markers of identity. We ask courtwatchers to note this information because (1) courts are unlikely to disclose this information even if we requested every docket; and (2) the system operates based on an individual’s outward perception and expression, regardless of their stated identity, so demographic observations are a reasonable methodology for this particular project. We again reiterate that courtwatchers can select as many racial demographic markers as apply.

[2] Because of limited capacity of the CourtWatch MA team, we again did not verify every case against the limited available charge information on masscourts.org. We have verified the charge in any case where the courtwatcher left the charge blank, did not hear the charge, or noted that reading the charge was waived in court. It is of course possible courtwatchers misheard the charge(s) in any given case; we reiterate that our data collection is not a substitute for open government and we are very hopeful that District Attorney Rollins will release data tracked by the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office with some regularity going forward.

[3] Courtwatchers write down demographic information (age, race, gender) based on observation alone; we recognize that this is an imperfect way to determine markers of identity. We ask courtwatchers to note this information because (1) courts are unlikely to disclose this information even if we requested every docket; and (2) the system operates based on an individual’s outward perception and expression, regardless of their stated identity, so demographic observations are a reasonable methodology for this particular project. We again reiterate that courtwatchers can select as many racial demographic markers as apply.

0 Comments

1/29/2019 1 Comment

The Weekly Digest: Our Methodology

We are publishing data from Court Watch every week on our website and also sharing that same information directly with the Rollins administration. We’re working to make the information sharing process consistent and transparent. To that end, we also want to make our process for collecting, cleaning, and analyzing the data consistent and transparent. Here’s how we do it:

Collecting Data

For the First 100 Days project, courtwatchers are trained to listen for specific information focused on charging and bail decisions. We created a single-page form courtwatchers can use to track this information for each hearing they observe. The data is later uploaded through an online form, so we advise courtwatchers that they may take notes however they like, provided they capture the information we’re tracking for each hearing they watch.

Entering Data

Courtwatchers are asked to enter their data directly into an online form themselves after each shift, preferably within 24 hours of observation. We’ve provided instructions on how to use the form. This method resolves issues with accuracy, capacity, and timeliness. Time and workloads don’t allow our three-person steering team to do data entry across hundreds of arraignments each week. The courtwatcher only has to read their own handwriting and recall their own experience, and given the turnaround time the memory is still fresh in their mind. And this efficient, people-powered method enables us to track and release data in real time on twitter and in the weekly digest. We are really thankful that courtwatchers have been willing and able to do this. We're doing it this way in order to offer our community and the Rollins administration the opportunity in real time to address injustices in the courts, rather than writing a report months later, as well as to document the pace of change.

Reviewing, Cleaning, and Analyzing Data

Because DA Rachael Rollins was inaugurated on a Wednesday, we pull and analyze weekly data for periods stretching from Wednesday of one week to Tuesday of the following week.

We download an excel spreadsheet of all the form responses input online and keep copies of each week’s master spreadsheet to avoid issues with cleaning things up within the online interface itself. Here’s the process:

Step 1 – narrow the period: we delete any entries that don’t apply to the week we’re working on. (e.g. tests from December, the prior week(s), etc.)

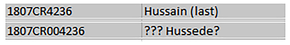

Step 2 – de-duplicate: Sometimes more than one volunteer observes each arraignment, but we only want each person being arraigned/each case to appear in the dataset once. Therefore, in excel we organize by date/court/defendant name so we can easily spot duplicate arraignments based on the defendant’s name and docket number. In order to be able to go back to earlier versions, we save a second copy of the worksheet where the duplicates will be deleted, and then manually clean the data—removing those extra entries after making sure to consolidate any info across the two watchers that is relevant to preserve.

Sometimes the process takes some creativity because courtwatchers didn’t quite catch the name or wrote down dramatically different spellings. This is why docket numbers can be especially helpful in cleaning the data. However, docket numbers aren’t always announced and courtwatchers don’t always catch them.

We download an excel spreadsheet of all the form responses input online and keep copies of each week’s master spreadsheet to avoid issues with cleaning things up within the online interface itself. Here’s the process:

Step 1 – narrow the period: we delete any entries that don’t apply to the week we’re working on. (e.g. tests from December, the prior week(s), etc.)

Step 2 – de-duplicate: Sometimes more than one volunteer observes each arraignment, but we only want each person being arraigned/each case to appear in the dataset once. Therefore, in excel we organize by date/court/defendant name so we can easily spot duplicate arraignments based on the defendant’s name and docket number. In order to be able to go back to earlier versions, we save a second copy of the worksheet where the duplicates will be deleted, and then manually clean the data—removing those extra entries after making sure to consolidate any info across the two watchers that is relevant to preserve.

Sometimes the process takes some creativity because courtwatchers didn’t quite catch the name or wrote down dramatically different spellings. This is why docket numbers can be especially helpful in cleaning the data. However, docket numbers aren’t always announced and courtwatchers don’t always catch them.

Step 3 – verify charges: then we sift through the open-ended charges box, back-filling anything that is a “decline to prosecute” charge and wasn’t properly entered. We also make sure that every entry includes the charge the person was facing; we do this by manually scanning every row of data to be sure at least one charge is filled in, and make sure it doesn’t get counted or categorized inaccurately. Because of limited capacity of the CourtWatch MA team, we cannot verify every case against the limited available charge information on masscourts.org. We verify the charge in any case where the courtwatcher left the charge blank, indicated they did not hear the charge, or noted that reading the charge was waived in court. It is of course possible courtwatchers mishear the charge(s) in any given case; our data collection represents our trained volunteers' best efforts and is not a substitute for open government. We are very hopeful that DA Rollins will release data tracked by the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office and make it publicly available for community review, much like State’s Attorney Kim Foxx in Cook County, IL. During this step, we also try to weed out cases that aren’t actually arraignments, like status hearings / restraining orders / probation violations. We also try to separate out specific dockets when a person was appearing for multiple open cases. If the courtwatcher noted a specific disposition by docket, we separate those cases into separate rows so we can track outcomes across each case in the dataset.

Step 4 – count the total number of cases: we use this second, de-duplicated version of the data, once cleaned, to get a total tally of the unique arraignments observed for that week. We also use this version to run comparison questions to the decline to prosecute (“DTP”) subset of cases.

Each week we start with more than 200 rows of data, but after cleaning and categorizing we review an average (over these past 3 weeks) of 86 cases in the DTP subset.

Step 4 – count the total number of cases: we use this second, de-duplicated version of the data, once cleaned, to get a total tally of the unique arraignments observed for that week. We also use this version to run comparison questions to the decline to prosecute (“DTP”) subset of cases.

Each week we start with more than 200 rows of data, but after cleaning and categorizing we review an average (over these past 3 weeks) of 86 cases in the DTP subset.

Number of Rows of Data for the Week at Initial Download |

Total Number of Cases after Cleaning |

Number of Cases in Decline to Prosecute Subset |

|

Week 1 |

232 |

176 |

79 |

Week 2 |

289 |

198 |

98 |

Week 3 |

239 |

161 |

82 |

So far there have been hundreds of cases we have not critically examined because we lack capacity to review them and they are not the focus of our project; however, it would be incredibly illuminating if Suffolk County made these data public.

Step 5 – DTP subset: finally, we create a third version of the data for cases with only charges on the DTP list. We find these cases based on whether the “other charges” field was left blank. If that field is empty, the row of data for that arraignment gets included in this third version of the dataset. Within that third version, we focus on outcomes, reorganizing the data so that a single column reflects whether the case was dismissed, diverted, bail was set, the person was released, or there was some other outcome. That makes it easier to get relevant tallies. Sometimes courtwatchers fill in two mutually exclusive fields regarding the disposition, so we read the open-ended comments to get a better sense of the actual outcome of the case and fill in the accurate information.

Since the administration has not released any official policies, we have had to try to figure out the difference between dismissal and diversion. As reflected in our week 3 digest, we have decided to try to differentiate between cases that end at that arraignment (a true dismissal) and cases where the person is required to come to another court date to fulfill a condition or show proof of compliance (diversion). We acknowledge these are judgement calls courtwatchers have to make in the moment and are grateful they approach their work so thoughtfully.

Step 6 – analyze: then we analyze. We write a bunch of functions in excel to get tallies for the number of charges, racial demographics, release decisions and dispositions, bail amounts, etc.

Step 7 – write the digest: finally, we take that analysis, put it into prose, and add charts and tables to present the data for public consumption.

Step 8 – respond & revise: the team reviews the data and offers some analysis as well as recommendations for how to address serious injustices volunteers witnessed that week and/or departures from the administration’s stated policy goals. And voila! We have a digest.

Step 9 – publicize & disseminate: we put the digest out over our twitter account (@CourtWatchMA) and highlight some of the most significant findings in a thread. This complements our daily stories from court, which we find by reading through open-ended comments courtwatchers have recorded in our online data collection form each morning. Follow along with the hashtags #first100days and #storiesfromcourt.

1/23/2019 1 Comment

Arraignments: What, Why, & Who

For the First 100 Days project, we have asked courtwatchers to watch and record observations at arraignments. We want to make sure community members understand what our volunteers are witnessing, so we have drafted this post giving an overview of arraignments.

In Massachusetts, anyone arrested must be arraigned within 24 hours of arrest or the next business day. They will arrive either from the police station in shackles or come in on their own two feet if they were able to post bail or were released on personal recognizance. Bail at the police station is set by a court clerk. People appearing at arraignments may also have been issued a summons.

In Massachusetts, anyone arrested must be arraigned within 24 hours of arrest or the next business day. They will arrive either from the police station in shackles or come in on their own two feet if they were able to post bail or were released on personal recognizance. Bail at the police station is set by a court clerk. People appearing at arraignments may also have been issued a summons.

What happens at an arraignment?

An arraignment is an accused person’s first appearance in front of a judge once a criminal allegation has been made and complaint has been issued. The purpose of this appearance is to formally charge someone with a crime, or divert or dismiss the case, appoint a lawyer if that is necessary, and decide conditions of release if the case proceeds as a criminal matter.

Our First 100 Days project is focused on observing arraignments in BMC Central, Roxbury, and Dorchester – all district court divisions of Boston Municipal Court in Suffolk County, MA. Read more about the project’s design and goals.

Our First 100 Days project is focused on observing arraignments in BMC Central, Roxbury, and Dorchester – all district court divisions of Boston Municipal Court in Suffolk County, MA. Read more about the project’s design and goals.

An arraignment is the opening of a criminal case. Initial charging and bail decisions control cases, and they're often handled by the least experienced prosecutors in an office.[1] In the words of Scott Hechinger, Director of Policy & Senior Staff Attorney at Brooklyn Defender Services, "arraignments are outcome determinative." Defense attorneys know this, but so do prosecutors.

Former Suffolk County Assistant District Attorney Adam John Foss has also spoken about the significance of arraignments. In an interview on the New Thinking podcast with Matt Watkins of the Center for Court Innovation, he said: “[I]t’s the arraignment, it’s this first touch with the criminal justice system. Or maybe it's your seventeenth touch, but whatever it is . . . It’s so consequential—to everything; whether you’re charged with a misdemeanor or felony; whether you’re charged with something that has a collateral consequence, which down the road is going to make it difficult for you to be doing the thing that we want you to do. I could charge you with an armed robbery, or I could charge you with larceny from a person. Those sorts of decisions are made by very junior prosecutors who are just trying to survive in an office where their metric system is ‘Don’t screw up.’”

We are observing arraignments to see whether the charges DA Rollins pledged to decline are actually being dismissed or diverted, but we are also observing arraignments to see how our neighbors are treated, including how people are charged and decisions about bail.

Former Suffolk County Assistant District Attorney Adam John Foss has also spoken about the significance of arraignments. In an interview on the New Thinking podcast with Matt Watkins of the Center for Court Innovation, he said: “[I]t’s the arraignment, it’s this first touch with the criminal justice system. Or maybe it's your seventeenth touch, but whatever it is . . . It’s so consequential—to everything; whether you’re charged with a misdemeanor or felony; whether you’re charged with something that has a collateral consequence, which down the road is going to make it difficult for you to be doing the thing that we want you to do. I could charge you with an armed robbery, or I could charge you with larceny from a person. Those sorts of decisions are made by very junior prosecutors who are just trying to survive in an office where their metric system is ‘Don’t screw up.’”

We are observing arraignments to see whether the charges DA Rollins pledged to decline are actually being dismissed or diverted, but we are also observing arraignments to see how our neighbors are treated, including how people are charged and decisions about bail.

Who's who in the courtroom?

Clerk

The Clerk usually sits or stands in front of or to the side of the Judge. They call the courtroom to order and call each case by the docket number and the defendant’s name. The Clerk also reads the charges against the person being prosecuted. It’s the Clerk’s job to record and then read back every decision the Judge makes about each case, including the next court date.

Court Officer

Court Officers stand in the gallery or on the floor of the courtroom. They wear uniforms with badges. Court Officers monitor the behavior of the people in the courtroom and may warn people or ask them to leave for things like using a cell phone or wearing a hat. They are responsible for bringing people into the courtroom who are being held in detention and for giving defendants any paperwork from the court.

Judge

The Judge is announced by the Clerk before they enter the courtroom. They sit at the front of the courtroom on a raised bench, higher than everybody else in the room. At an arraignment, the Judge listens to arguments and makes a bail determination. The judge makes all legal decisions in the courtroom. This includes setting bail conditions including (but not limited to) money bail, GPS shackling, stay away orders, or drug testing and treatment. The judge also decides any motions asked for by either the assistant district attorney (“ADA”), the probation department, or the defense attorney. These might include motions to revoke bail if the defendant is out on bail for any other cases and motions to request a 58A hearing (otherwise known as a separate “dangerousness hearing”). The judge can also decide to accept or deny any other recommendation or resolution before the court including recommendations for dismissal and dismissal pending conditions like a fine, pretrial diversion, or the reduction of the offense to a civil infraction. Judges can set bail higher than, lower than, or equal to the prosecutor’s recommendation, release the individual on personal recognizance, or dismiss the case entirely. The person’s next appearance in court is set around the judge’s (and attorneys’) schedule.

Probation

The Probation Officer typically sits either to the side of or slightly behind the Judge and Clerk, often at a desk with a computer. They often face towards the gallery. Probation is responsible for managing the criminal court records of everyone accused of a crime. When a person is arraigned, probation will run their CORI (Criminal Offender Record Information) and tell the judge if the person is currently on probation and if probation wants to move for a violation of the person’s probation. People who are being arraigned and not in custody are asked to check in with the probation department at the courthouse before their arraignment. Probation will collect their name and contact information and interview them to determine if they’re eligible for a court appointed attorney.

Assistant District Attorney (“ADA”)

There are usually between 1 and 3 Assistant District Attorneys (“ADAs”) sitting or standing at a table in the courtroom in front of the judge. ADAs are prosecutors, lawyers “for the Commonwealth.” ADAs represent the state’s interest in court and communicate directly with the police about charges. At arraignment, ADAs tell the court a story about the case based on the police report; decide what to tell the court from the person’s CORI to summarize the criminal history of the person being prosecuted; and make recommendations to the court about bail and argue motions. ADAs can also conference with defense attorneys about resolving cases at arraignment.

Defendant (person being accused of a crime)

The person appearing for arraignment may be sitting in the gallery or they may be in custody in a jail cell above or below the courtroom. When their name is called, the person being prosecuted will be asked to stand and come forward, or they will be brought into the courtroom in handcuffs into what’s referred to as the “dock,” which is a holding area usually behind Plexiglas and a locked door. The defendant is the person being formally charged with a crime and prosecuted.

Defense Attorney

The defense attorney is usually sitting or standing at the table nearest to the “dock.” There are normally several defense attorneys sitting behind the table. Defense attorneys represent people being accused of crimes. They are responsible for zealously advocating for and protecting the best interests of their clients. At arraignments, defense attorneys argue against prosecutors for lower or no bail and the least restrictive conditions of release. Defense attorneys can also argue motions at arraignment, like motions to dismiss or reduce the charges.

If probation determines that the person being prosecuted is “indigent” (can’t afford to pay a private attorney) then they will be assigned a public defender. There are two kinds of public defenders:

The Clerk usually sits or stands in front of or to the side of the Judge. They call the courtroom to order and call each case by the docket number and the defendant’s name. The Clerk also reads the charges against the person being prosecuted. It’s the Clerk’s job to record and then read back every decision the Judge makes about each case, including the next court date.

Court Officer

Court Officers stand in the gallery or on the floor of the courtroom. They wear uniforms with badges. Court Officers monitor the behavior of the people in the courtroom and may warn people or ask them to leave for things like using a cell phone or wearing a hat. They are responsible for bringing people into the courtroom who are being held in detention and for giving defendants any paperwork from the court.

Judge

The Judge is announced by the Clerk before they enter the courtroom. They sit at the front of the courtroom on a raised bench, higher than everybody else in the room. At an arraignment, the Judge listens to arguments and makes a bail determination. The judge makes all legal decisions in the courtroom. This includes setting bail conditions including (but not limited to) money bail, GPS shackling, stay away orders, or drug testing and treatment. The judge also decides any motions asked for by either the assistant district attorney (“ADA”), the probation department, or the defense attorney. These might include motions to revoke bail if the defendant is out on bail for any other cases and motions to request a 58A hearing (otherwise known as a separate “dangerousness hearing”). The judge can also decide to accept or deny any other recommendation or resolution before the court including recommendations for dismissal and dismissal pending conditions like a fine, pretrial diversion, or the reduction of the offense to a civil infraction. Judges can set bail higher than, lower than, or equal to the prosecutor’s recommendation, release the individual on personal recognizance, or dismiss the case entirely. The person’s next appearance in court is set around the judge’s (and attorneys’) schedule.

Probation

The Probation Officer typically sits either to the side of or slightly behind the Judge and Clerk, often at a desk with a computer. They often face towards the gallery. Probation is responsible for managing the criminal court records of everyone accused of a crime. When a person is arraigned, probation will run their CORI (Criminal Offender Record Information) and tell the judge if the person is currently on probation and if probation wants to move for a violation of the person’s probation. People who are being arraigned and not in custody are asked to check in with the probation department at the courthouse before their arraignment. Probation will collect their name and contact information and interview them to determine if they’re eligible for a court appointed attorney.

Assistant District Attorney (“ADA”)

There are usually between 1 and 3 Assistant District Attorneys (“ADAs”) sitting or standing at a table in the courtroom in front of the judge. ADAs are prosecutors, lawyers “for the Commonwealth.” ADAs represent the state’s interest in court and communicate directly with the police about charges. At arraignment, ADAs tell the court a story about the case based on the police report; decide what to tell the court from the person’s CORI to summarize the criminal history of the person being prosecuted; and make recommendations to the court about bail and argue motions. ADAs can also conference with defense attorneys about resolving cases at arraignment.

Defendant (person being accused of a crime)

The person appearing for arraignment may be sitting in the gallery or they may be in custody in a jail cell above or below the courtroom. When their name is called, the person being prosecuted will be asked to stand and come forward, or they will be brought into the courtroom in handcuffs into what’s referred to as the “dock,” which is a holding area usually behind Plexiglas and a locked door. The defendant is the person being formally charged with a crime and prosecuted.

Defense Attorney

The defense attorney is usually sitting or standing at the table nearest to the “dock.” There are normally several defense attorneys sitting behind the table. Defense attorneys represent people being accused of crimes. They are responsible for zealously advocating for and protecting the best interests of their clients. At arraignments, defense attorneys argue against prosecutors for lower or no bail and the least restrictive conditions of release. Defense attorneys can also argue motions at arraignment, like motions to dismiss or reduce the charges.

If probation determines that the person being prosecuted is “indigent” (can’t afford to pay a private attorney) then they will be assigned a public defender. There are two kinds of public defenders:

- Bar Advocate – A bar advocate is a private attorney who is paid by the hour on a contract basis to take court appointed cases.

- CPCS Attorney – Attorneys who receive a salary from the Committee for Public Counsel Services, a government agency paid for by a line item in the state budget. CPCS has offices in every county. Each office has a social worker, an investigator, and a team of lawyers.

Final Thoughts

While people may have to wait in court for a long time for their name to be called, arraignments happen quickly and can be very hard to follow and hear. Usually people have only had a few moments to talk to their lawyer beforehand. Prosecutors have also had almost no time to review cases. People who have been in custody have not been able to shower, change clothes, communicate with family or employers, take care of pets, or take their medication.

If you’ve never observed an arraignment and would like to get a sense of the proceeding, you can read sample fake arraignment scripts here. You can also sign up for our next courtwatch training!

If you’ve never observed an arraignment and would like to get a sense of the proceeding, you can read sample fake arraignment scripts here. You can also sign up for our next courtwatch training!

[1] In some cases, the Commonwealth is represented in court by law students under the direction of Assistant District Attorneys through the Suffolk University Law School Prosecutors Program. These “student prosecutors” primarily handle arraignments, bail/detention hearings, and pre-trial motions.

1/18/2019 3 Comments

The Second Week

From January 9th to January 15th, our courtwatchers observed 193 individual people facing charges across three divisions of Boston Municipal Court (BMC Central, Roxbury, and Dorchester).[1] Some of these people had multiple open cases. Courtwatchers observed 198 cases in which they documented a specific outcome.

This week, roughly half of the cases observed (49.49%) involved only charges that Suffolk County District Attorney Rachael Rollins has pledged to decline to prosecute, either by dismissing at arraignment or diverting through a non-criminal proceeding, program, or outcome. Again, that means half of the cases we observed processed by our criminal courts this week represented crimes that District Attorney Rollins has identified as low-level, non-violent crimes rooted in poverty, mental illness, and addiction.

Our digest will focus on the data courtwatchers collected about cases that exclusively involved charges from DA Rollins’ Decline to Prosecute list.[2]

This week, roughly half of the cases observed (49.49%) involved only charges that Suffolk County District Attorney Rachael Rollins has pledged to decline to prosecute, either by dismissing at arraignment or diverting through a non-criminal proceeding, program, or outcome. Again, that means half of the cases we observed processed by our criminal courts this week represented crimes that District Attorney Rollins has identified as low-level, non-violent crimes rooted in poverty, mental illness, and addiction.

Our digest will focus on the data courtwatchers collected about cases that exclusively involved charges from DA Rollins’ Decline to Prosecute list.[2]

There were 98 cases involving ONLY charges on the decline to prosecute list.

In cases of conditional dismissals, individuals were frequently required to report back to court on a future date to prove compliance with the condition—even when that compliance took the form of payment of a fee to the court itself, which the court should be able to verify on its own. When people are required to appear in court, it may mean they have to take time off work, school, or parenting, or pay for transportation to make it there which can be a challenge for working class families.

- 42% of these cases (41 cases) advanced as criminal matters.

- 51 of these cases were dismissed at arraignment.

- 6 of these cases were diverted at arraignment

- Therefore, a total of 57 cases, or roughly 58%, were declined within the meaning of DA Rollins’ campaign pledge.

In cases of conditional dismissals, individuals were frequently required to report back to court on a future date to prove compliance with the condition—even when that compliance took the form of payment of a fee to the court itself, which the court should be able to verify on its own. When people are required to appear in court, it may mean they have to take time off work, school, or parenting, or pay for transportation to make it there which can be a challenge for working class families.

*A note on terms: the distinction between diversion and conditional dismissal is a gray area. In her campaign, Rachael Rollins used both terms. We ask courtwatchers to try to distinguish between the two and report their categorizations based on what they observe and hear in court, but it may be a distinction without a difference. We’re trying to decipher what the administration considers the difference based on what terms are being used in court by prosecutors.*

What gets dismissed?

Just as we saw last week, the vast majority of dismissals were driving cases – 41 of the 51 cases (80%) that were dismissed. The other 10 cases dismissed at arraignment were incidents of: Trespass (4); Disorderly Conduct (1); Drug Possession (3); and Shoplifting (2).

A substantial majority of driving cases were dismissed this week at arraignment.

A substantial majority of driving cases were dismissed this week at arraignment.

|

|

Driving Charges (50 total)

|

|

|

Dismissed

|

41

|

80%

|

|

Diverted

|

(zero)

|

0%

|

|

Released on Personal Recognizance

|

6

|

12%

|

|

Other Outcome

(bail set, arraignment continued, not resolved before courtwatcher left) |

3

|

6%

|

What gets diverted?

|

|

Diverted Cases (6 total)

|

|

|

Charges

|

Type of Diversion

|

Outcome

|

|

Trespass & Disturbing the Peace

|

Community Service

|

100 hours

|

|

Drug Possession

|

Community Service

|

16 hours within 60 days

|

|

Drug Possession

|

Drug Treatment

|

|

|

Disorderly Conduct

|

Community Service

|

8 hours within 3 weeks

|

|

Trespass

|

Court Costs

|

$150 within a week

|

|

Disorderly Conduct

|

Community Service

|

12 hours within 30 days

|

Release or Detention Decisions

- In 26 cases that advanced as criminal matters, the person being arraigned was released on personal recognizance. In many such cases, the court also imposed conditions—especially common was a stay away or no contact order for the place of the incident or a person involved.

- In 8 of these cases, bail was set. Bail amounts ranged from $150 to $2,500.

- In 1 case, the ADA asked for personal recognizance for a man charged with receiving stolen property and larceny under $1200 for allegedly stealing a coat, but Judge Sally Kelly set $150 bail anyway. Read more here.

- In 1 case, in addition to the $2,500 bail, the judge imposed a GPS (e-shackle / electronic monitor), set a 6 PM – 6 AM curfew, and demanded the person being arraigned surrender their passport. This person was charged with possession with intent to distribute. There were two co-defendants in this case, and they all live together. The ADA originally asked for a stay away/no contact order, but withdrew that condition when she learned they all live together, realizing it would be functionally impossible to follow.

ADAs’ bail recommendations are incredibly influential because they set the tone of the conversation about the case. Judges ask ADAs to make their bail recommendation first, before the defense attorney has the opportunity to speak.

ADAs often asked for bails equal to or higher than the judge ultimately imposed. Again, ADAs get to direct the conversation on bail, so a judge’s decision to set bail at all and to set a specific amount is significantly informed by the ADA.

In two of the cases where the judge didn’t flatly adopt the ADA’s recommendation, the judge set exactly half the bail amount the ADA requested. This is significant because it suggests the judge simply split the difference between release on personal recognizance requested by the defense and the ADA bail recommendation. Bail should be tailored to getting someone to return to court and, by law, must factor in the person’s ability to pay. It should not be a knee-jerk compromise.

In the remaining 7 cases, we don’t know the release decision or case outcome because the courtwatcher left before the judge resumed hearing the case, the arraignment was continued, or the person being arraigned remained detained (in one case despite the judge deciding to release them on personal recognizance on the pending trespass & drug possession charges) in order to resolve a warrant in another court.

In the remaining 7 cases, we don’t know the release decision or case outcome because the courtwatcher left before the judge resumed hearing the case, the arraignment was continued, or the person being arraigned remained detained (in one case despite the judge deciding to release them on personal recognizance on the pending trespass & drug possession charges) in order to resolve a warrant in another court.

The charge breakdowns are as follows [keep in mind that some folks had multiple charges]:

|

Charge

|

Number of Cases

|

|

Trespass

|

10

|

|

Shoplifting

|

7

|

|

Larceny under $1200

|

6

|

|

Disorderly Conduct

|

5

|

|

Disturbing the Peace

|

1

|

|

Receiving Stolen Property

|

3

|

|

Driving Cases (suspended or revoked license or registration)

|

50

|

|

Breaking and Entering for the purpose of shelter

|

(zero)

|

|

Wanton/Malicious Destruction of Property

|

1

|

|

Threats (not domestic violence related)

|

1

|

|

Minor in Possession of Alcohol

|

(zero)

|

|

Drug Possession

|

17

|

|

Drug Possession with Intent to Distribute

|

5

|

|

Resisting Arrest

|

(zero)

|

In 18 of these cases, the person being arraigned was in jail at the time of arraignment. Among those 18 individuals,

In other words, 11 people spent time in jail and ultimately were not prosecuted or were released; they were detained without an ability to shower, change clothes, see their kids, walk their pets, take their medications, or communicate with their jobs or families—only to have a judge determine there was no good reason to detain them.

- 8 were released on personal recognizance,

- 1 had their case diverted (charge was disorderly conduct), and

- 2 had their cases dismissed (charges were disorderly conduct & shoplifting).

In other words, 11 people spent time in jail and ultimately were not prosecuted or were released; they were detained without an ability to shower, change clothes, see their kids, walk their pets, take their medications, or communicate with their jobs or families—only to have a judge determine there was no good reason to detain them.

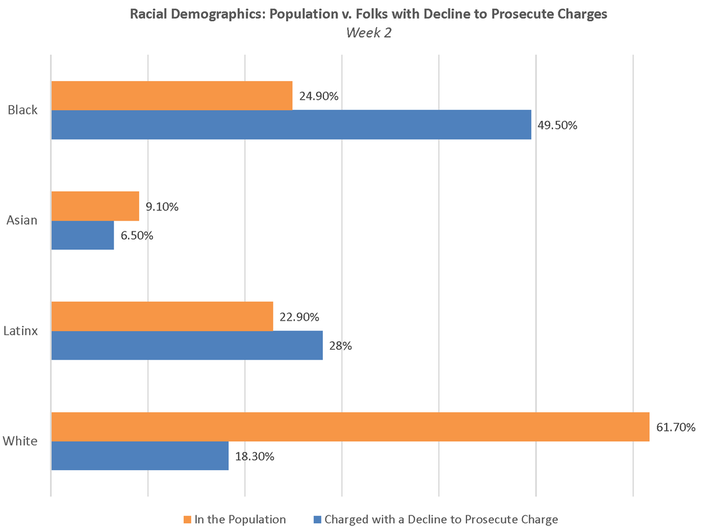

Demographics[3] – Who is Prosecuted for these Offenses? |

|

Of the 93 declination cases observed this week in which courtwatchers noted demographic information, the racial breakdown of the people arraigned was as follows:

49.5% Black, 28% Latinx; 18.3% white, 5.4% East Asian, and 1.1% South Asian. |

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the demographics of Suffolk County are as follows:

24.9% Black or African American, 22.9% Hispanic of Latino, 61.7% white, 9.1% Asian, 3.4% two or more races, .7% Native American or Alaskan Native and .2% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander |

Black and Latinx defendants are once again starkly overrepresented compared to the population, while white defendants are starkly underrepresented.

Whose cases get dismissed or diverted?

We wondered about the racial breakdown of dismissals and diversion as compared to the entire group of cases involving only charges to be declined. Basically, if you're white, are you more likely to have your case get dismissed or diverted?

In fact, the racial demographic breakdowns are remarkably similar, and the percentage of white folks whose cases get dismissed/diverted is lower than the whole decline to prosecute dataset, meaning comparatively fewer white folks are having their cases dismissed or diverted.

Decline to Prosecute Racial Demographics: Week 2

49.5% Black, 28% Latinx; 18.3% white; 5.4% East Asian; and 1.1% South Asian.

Dismissed/Diverted Racial Demographics: Week 2

50% Black; 30.4% Latinx; 12.5% white; 5.3% East Asian; and 1.8% South Asian.

However, this finding does not suggest that ADAs are showing special leniency to non-white individuals. The vast majority of cases which get dismissed or diverted are driving cases. These kinds of offenses are disparately enforced from the outset, by police. We suspect white folks are not being stopped by police as often, and certainly not arrested as often, for driving offenses, and that’s where the underlying disparity exists.

A substantial body of research – from academic studies to opinions by our own Supreme Judicial Court – confirms that white people are not arrested nearly as often for minor crimes and driving offenses in Boston, in Massachusetts, and in the U.S. in its entirety.[4]

In fact, the racial demographic breakdowns are remarkably similar, and the percentage of white folks whose cases get dismissed/diverted is lower than the whole decline to prosecute dataset, meaning comparatively fewer white folks are having their cases dismissed or diverted.

Decline to Prosecute Racial Demographics: Week 2

49.5% Black, 28% Latinx; 18.3% white; 5.4% East Asian; and 1.1% South Asian.

Dismissed/Diverted Racial Demographics: Week 2

50% Black; 30.4% Latinx; 12.5% white; 5.3% East Asian; and 1.8% South Asian.

However, this finding does not suggest that ADAs are showing special leniency to non-white individuals. The vast majority of cases which get dismissed or diverted are driving cases. These kinds of offenses are disparately enforced from the outset, by police. We suspect white folks are not being stopped by police as often, and certainly not arrested as often, for driving offenses, and that’s where the underlying disparity exists.

A substantial body of research – from academic studies to opinions by our own Supreme Judicial Court – confirms that white people are not arrested nearly as often for minor crimes and driving offenses in Boston, in Massachusetts, and in the U.S. in its entirety.[4]

Beyond the Charges to Be Declined: Other Charges

As a point of interest, we emphasize that a significant number of the “other” cases also exclusively involved minor matters. For example, 12 of the 100 cases reflecting charges not on the declination list were for jurors who failed to appear for jury duty—most of them because they thought they were ineligible. An additional 11 of these 100 cases involved some kind of default removal – for example, missed court dates or failure to prove completion of community service. Many of those defaults were cleared and almost all of the jury cases were dismissed prior to arraignment.

Cause for Concern: Practices to Change

As stated above, 41 cases involving only charges to be declined were not dismissed or diverted. Those cases should also be declined, and we hope this will change in the weeks to come.

Courtwatchers observed 1 declination case involving a charge of Wanton/Malicious Destruction of Property in which an ADA asked for $500 bail but the judge ultimately released the individual on personal recognizance.

In the 8 declination cases in which an ADA requested bail this week, the judge imposed bail 7 out of those 8 times—a rate of 87.5%. ADAs have a tremendous amount of influence over bail.

We again emphasize that ADAs should always recommend release on personal recognizance in cases when the person is not a flight risk and should never request bail for charges that are on the do not prosecute list.

Courtwatchers observed 1 declination case involving a charge of Wanton/Malicious Destruction of Property in which an ADA asked for $500 bail but the judge ultimately released the individual on personal recognizance.

In the 8 declination cases in which an ADA requested bail this week, the judge imposed bail 7 out of those 8 times—a rate of 87.5%. ADAs have a tremendous amount of influence over bail.

We again emphasize that ADAs should always recommend release on personal recognizance in cases when the person is not a flight risk and should never request bail for charges that are on the do not prosecute list.

Takeaways: Reactions from the CourtWatch MA team

We appreciate that District Attorney Rollins continues to give interviews focused on the importance of declining the 15 crimes she has identified as criminalizing poverty, addiction, and mental illness.

But as this week’s findings again demonstrate, her office is still actively prosecuting people for these crimes. In many cases, even if the charge is dismissed at arraignment that dismissal comes with conditions, whether court costs or community service hours.

We have concerns about these conditions. While we support DA Rollins’ pledge to not criminally prosecute people for being poor or suffering from addiction or mental illness, in many cases these folks are similarly burdened by court conditions, whether a fine/fee or community service. As traditionally implemented by our court system, community service is highly prescribed manual labor. Even when a person is given the option to serve at a nonprofit of their choosing, community service may be difficult to complete if that person works, has kids, or doesn't have a car. Finally, judges and ADAs alike have misconceptions about what it means to require someone to complete community service hours through the state program.

But as this week’s findings again demonstrate, her office is still actively prosecuting people for these crimes. In many cases, even if the charge is dismissed at arraignment that dismissal comes with conditions, whether court costs or community service hours.

We have concerns about these conditions. While we support DA Rollins’ pledge to not criminally prosecute people for being poor or suffering from addiction or mental illness, in many cases these folks are similarly burdened by court conditions, whether a fine/fee or community service. As traditionally implemented by our court system, community service is highly prescribed manual labor. Even when a person is given the option to serve at a nonprofit of their choosing, community service may be difficult to complete if that person works, has kids, or doesn't have a car. Finally, judges and ADAs alike have misconceptions about what it means to require someone to complete community service hours through the state program.

We look forward to a public release of office policy that will give Assistant District Attorneys guidance on how to carry out DA Rollins’ vision.

And we emphasize that our method of data collection carries many imperfections which would be resolved by a public release of the data her office already tracks.

[1] This count may include a handful of status hearings, restraining orders, or other types of hearings that were not initial arraignments. By our best estimation based on the data we collected, this week’s observed cases involved 207 unique dockets. However, courtwatchers did not always record disposition by individual docket, more often noting the hearing outcome by defendant even when they wrote down multiple docket numbers. Further, we note that the total number of hearings observed is not the total number of arraignments which transpired in those courts. For a full count of arraignments, you can view sparse information about all criminal cases, by court and date of filing, at masscourts.org. Select the court, use the “case type” tab, select the relevant date(s), and select both “criminal” and “criminal cross site” as the case type.

[2] Because of limited capacity of the CourtWatch MA team, we have not verified every case against the limited available charge information on masscourts.org. We have verified the charge in any case where the courtwatcher left the charge blank (roughly 15 cases out of 198), indicated they did not hear the charge, or noted that reading the charge was waived in court. It is of course possible courtwatchers misheard the charge(s) in any given case; our data collection is not a substitute for open government and we are very hopeful that District Attorney Rollins will release data tracked by the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office with some regularity going forward.

[3] Courtwatchers write down demographic information (age, race, gender) based on observation alone; we recognize that this is an imperfect way to determine markers of identity. We ask courtwatchers to note this information because (1) courts are unlikely to disclose this information even if we requested every docket; and (2) the system operates based on an individual’s outward perception and expression, regardless of their stated identity, so demographic observations are a reasonable methodology for this particular project.

[4] Commonwealth v. Warren, 475 Mass. 530, 539–40 (2016); Jeffrey Fagan et al., Final Report, An Analysis of Race and Ethnicity Patterns in Boston Police Department and Field Interrogation, Observation, Frisk, and/or Search Reports 2 (June 15, 2015); ACLU of Massachusetts, Black, Brown and Targeted (2014); Amy Farrell, et al. Massachusetts Racial and Gender Profiling Study, 24-27 (2004). Based on 2011 data, the Bureau of Justice Statistics found that Black drivers are more likely to be stopped, ticketed, and searched than white drivers, and more often for violations other than speeding, like a vehicle defect or a record check. See also generally Emma Pierson, et al., A Large-Scale Analysis of Racial Disparities in Police Stops Across the United States, 5-7, Stanford University (2017); David A. Harris, ACLU, Driving While Black: Racial Profiling on Our Nation’s Highways (1999). To differing degrees, this pattern of stopping and arresting people of color for “driving while Black” or “driving while Latinx” emerges around the country, from Philadelphia to Milwaukee to Illinois.

[2] Because of limited capacity of the CourtWatch MA team, we have not verified every case against the limited available charge information on masscourts.org. We have verified the charge in any case where the courtwatcher left the charge blank (roughly 15 cases out of 198), indicated they did not hear the charge, or noted that reading the charge was waived in court. It is of course possible courtwatchers misheard the charge(s) in any given case; our data collection is not a substitute for open government and we are very hopeful that District Attorney Rollins will release data tracked by the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office with some regularity going forward.

[3] Courtwatchers write down demographic information (age, race, gender) based on observation alone; we recognize that this is an imperfect way to determine markers of identity. We ask courtwatchers to note this information because (1) courts are unlikely to disclose this information even if we requested every docket; and (2) the system operates based on an individual’s outward perception and expression, regardless of their stated identity, so demographic observations are a reasonable methodology for this particular project.

[4] Commonwealth v. Warren, 475 Mass. 530, 539–40 (2016); Jeffrey Fagan et al., Final Report, An Analysis of Race and Ethnicity Patterns in Boston Police Department and Field Interrogation, Observation, Frisk, and/or Search Reports 2 (June 15, 2015); ACLU of Massachusetts, Black, Brown and Targeted (2014); Amy Farrell, et al. Massachusetts Racial and Gender Profiling Study, 24-27 (2004). Based on 2011 data, the Bureau of Justice Statistics found that Black drivers are more likely to be stopped, ticketed, and searched than white drivers, and more often for violations other than speeding, like a vehicle defect or a record check. See also generally Emma Pierson, et al., A Large-Scale Analysis of Racial Disparities in Police Stops Across the United States, 5-7, Stanford University (2017); David A. Harris, ACLU, Driving While Black: Racial Profiling on Our Nation’s Highways (1999). To differing degrees, this pattern of stopping and arresting people of color for “driving while Black” or “driving while Latinx” emerges around the country, from Philadelphia to Milwaukee to Illinois.

1/11/2019 1 Comment

The First Week

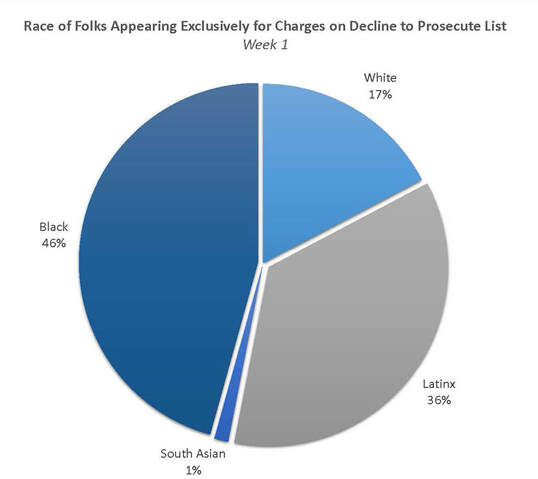

From January 2nd to January 8th, our courtwatchers observed 176 unique arraignments. Forty-five percent (45%) of those arraignments involved only charges that Suffolk County District Attorney Rachael Rollins has pledged to decline to prosecute, either by dismissing at arraignment or diverting through a non-criminal proceeding, program, or outcome.

The following data pertain to cases involving only these charges. We did not analyze cases that may have included a charge on this list as well as some other charge. Although courtwatchers are documenting “other charges” in an open-ended field, it is not the focus of this project to gather data about all cases. We are focused on seeing the transformation of arraignment court with respect to the charges which District Attorney Rollins pledged to decline.

The following data pertain to cases involving only these charges. We did not analyze cases that may have included a charge on this list as well as some other charge. Although courtwatchers are documenting “other charges” in an open-ended field, it is not the focus of this project to gather data about all cases. We are focused on seeing the transformation of arraignment court with respect to the charges which District Attorney Rollins pledged to decline.

Courtwatchers observed 79 cases involving ONLY charges on the decline to prosecute list.

- 27 of these cases were dismissed at arraignment

- 6 of these cases were diverted at arraignment

- Therefore, a total of 33 cases, or roughly 41%, were declined within the meaning of DA Rollins’ campaign pledge.

- That means that 59% of these cases remained criminal matters.

- Even when cases were dismissed or diverted, the disposition sometimes involved conditions, like drug treatment; a court fee; or probation.

What gets dismissed or diverted?

The vast majority of outright dismissals were driving cases – 21 of the 27 cases (78%) that our courtwatchers observed get dismissed. The other 6 cases which were dismissed at arraignment were incidents of: Trespass (2); Drug Possession (2); Shoplifting (1), and a default for failure to show proof of community service completion on an earlier case (1).

A majority of driving cases were dismissed or diverted this week at arraignment.

|

|

Driving Charges (35 total)

|

|

|

Dismissed

|

21

|

60%

|

|

Diverted

|

3

|

8.6%

|

|

Released on Personal Recognizance

|

7

|

20%

|

|

Other Outcome (Bail set, Pled guilty)

|

4

|

11.4%

|

Release or Detention Decision

In 36 of these cases, the person being arraigned was released on personal recognizance. In many such cases, the court also imposed conditions—especially common was a stay away or no contact order for the place of the incident or a person involved.

In 7 of these cases, bail was set. Bail amounts ranged from $40 to $700.

We do not know how one case resolved because the arraignment was pushed to later in the day and the courtwatcher left before the case resumed. Two cases resolved with some other outcome—in one case, a guilty plea on a driving offense resulting in 10 days house arrest (minus time served in jail); in another, a section 35 civil commitment.

In 7 of these cases, bail was set. Bail amounts ranged from $40 to $700.

We do not know how one case resolved because the arraignment was pushed to later in the day and the courtwatcher left before the case resumed. Two cases resolved with some other outcome—in one case, a guilty plea on a driving offense resulting in 10 days house arrest (minus time served in jail); in another, a section 35 civil commitment.

The charge breakdowns are as follows [keep in mind that some folks had multiple charges]:

|

Charge

|

Number of Cases

|

|

Trespass

|

10

|

|

Shoplifting

|

2

|

|

Larceny under $1200

|

5

|

|

Disorderly Conduct

|

3

|

|

Disturbing the Peace

|

(zero)

|

|

Receiving Stolen Property

|

1

|

|

Driving Cases

(suspended or revoked license or registration) |

35

|

|