|

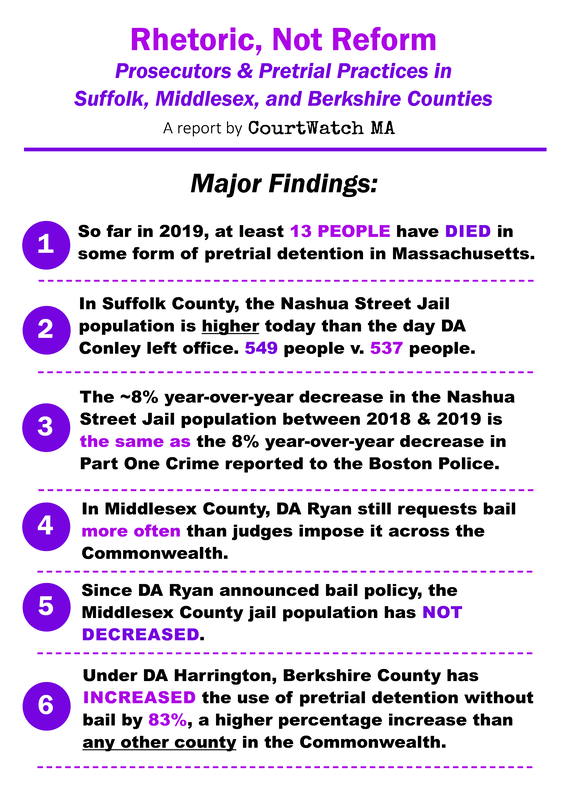

9/30/2019 3 Comments Rhetoric, Not Reform: Prosecutors & Pretrial Practices in Suffolk, Middlesex, and Berkshire CountiesThere’s a lot of talk about progressive prosecutors, good prosecutors, reform-minded prosecutors. As an abolitionist project, we care about how people are treated in court and, ultimately, eliminating the prosecuting office.

9/25/2019 3 Comments New Resource: Abolitionist Principles & Campaign Strategies for Prosecutor OrganizingThe organizations that came together to develop this framework were Community Justice Exchange, Court Watch MA, Families for Justice as Healing, Project NIA, and Survived and Punished NY.

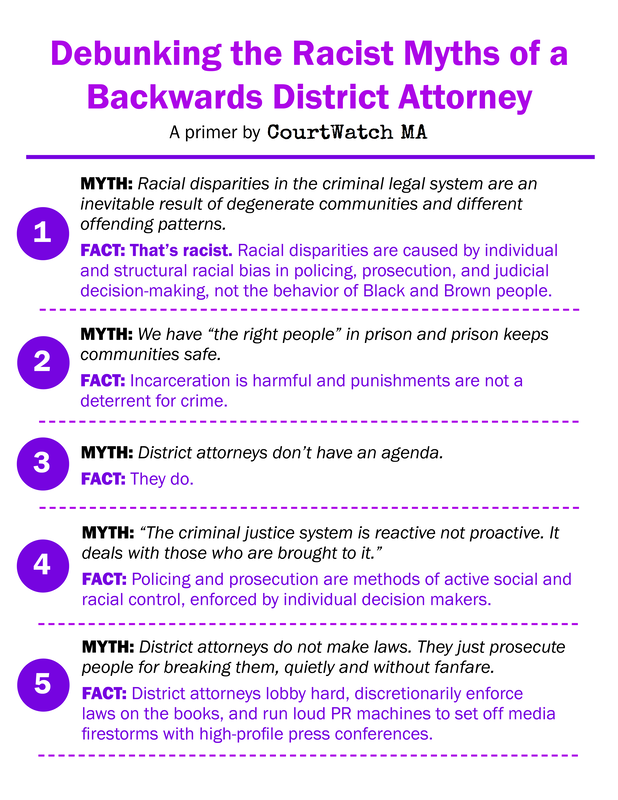

Thanks to Fahd Ahmed, Amna Akbar, Erin Miles Cloud, Lily Fahsi-Haskell, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Craig Gilmore, Joey Mogul, Andrea Ritchie, Lisa Sangoi, Dean Spade and others for reviewing and providing critical feedback. The following guide can be downloaded as a PDF document here. On Tuesday, May 28th, the Boston Globe published a virulently racist op-ed by Barnstable County’s District Attorney. Though he didn’t mention her by name, the op-ed targeted Suffolk County’s District Attorney, Rachael Rollins. This op-ed was one of many attacks on Rollins because she is a Black woman in a position of power threatening the status quo system designed to over-police, over-prosecute, and over-punish Black and Brown people. In a busy field of potential candidates, Suffolk County residents voted overwhelmingly for the most progressive candidate because of the changes DA Rollins committed to making: reducing racial disparities, rates of prosecution, and incarceration. As soon as DA Rollins announced policies to formalize her campaign promises, critics have cried out that the sky is falling and that public safety in the Commonwealth is in jeopardy, with no evidence to back up their claims. The loudest attacks have come from the EOPSS Secretary and the Barnstable County DA: two white Republican men with horrendous track records for their racist treatment of the residents they represent and the people under their control. Rollins has spoken publicly about the need for prosecutors to take responsibility for the intergenerational harm caused by contact with the criminal punishment system. Those attacking Rollins are intentionally masking the real power of district attorneys because they want to conduct business as usual without public scrutiny. Make no mistake, critics of decarceration have an agenda—to continue aggressively policing, prosecuting, and punishing Black and Brown people. CourtWatch MA is an accountability project, and for us, data is key. O’Keefe brags about being a “professional prosecutor” in the Boston Globe. If he wants to establish his credentials, he should release all of his prosecution data immediately. The limited data that are publicly accessible show that under O’Keefe’s leadership, Barnstable County boasted the absolute worst racial disparities in pre-trial detention of any Massachusetts jurisdiction—with Black people comprising 2.4% of the population but 25% of people jailed pre-trial. O’keefe relies on dangerous, racist tropes to demonize Black communities and justify decades-old practices that target Black and Brown people. The Globe should have rejected his piece. His bald, biased assertions are patently false. MYTH: Racial disparities in the criminal legal system are an inevitable result of degenerate communities and different offending patterns. FACT: That’s racist. Racial disparities are caused by individual and structural racial bias in policing, prosecution, and judicial decision-making, not the behavior of Black and Brown people. Research overwhelmingly shows that racial disparities in the criminal punishment system result from system actors, not from differences in individual behavior or community values. O’Keefe employs overt stereotypes to shame and blame Black and Brown communities. His racist assault on DA Rollins uses language harkening back to the Moynihan Report that blamed Black mothers for a “ghetto culture,” criminalized poverty, and ushered in decades of expansion of police, prosecutors, and prisons. Far too many prosecutors around the country continue to demonize people of color as inherently “violent” and “criminal” in order to justify their ever-expanding power to surveil, control, and punish, and to absolve themselves of responsibility for racial disparities in the criminal punishment system. These prosecutors blame Black communities for “moral failings” instead of recognizing the role of intentional state policy, and especially their own role, in creating and reinforcing toxicity, trauma, and structural racism. Even those who recognize that poor communities of color have been systematically deprived of resources use that fact to explain crime, not criminalization, policing, and prosecution. Suffolk County voters created a mandate for DA Rollins to push back on these narratives and confront decades of failed policies from the war on drugs and the war on poor communities of color. MYTH: We have “the right people” in prison and prison keeps communities safe. District attorneys often argue that sentencing people to jail and prison is necessary to keep communities safe. Research shows that terms of incarceration create trauma, harm, and do not prevent crime. While Massachusetts has a low rate of incarceration relative to other states, we still incarcerate more people here than most countries around the world and we have among the highest racial disparities in incarceration. The idea that we have the right people in prison is therefore also racist. Tens of thousands more people are harmed by the criminal punishment system every year, including many thousands who don’t end up in prison. In 2017, there were more than 62,000 pre-trial admissions and releases from Massachusetts jails. According to the Prison Policy Initiative, roughly 61,000 people are on probation in Massachusetts. Incarceration is harmful and destroys all of the elements that contribute to a safe community. Public safety policy should enable people to access safe and supportive housing, treatment, healthcare, employment, and education. Traditional prosecutions make us less safe because open cases, incarceration, and criminal records are barriers between people and what they need to live well. Again: prison is only a piece of this. Putting people in jail pre-trial disrupts their lives and livelihoods: family responsibilities; education; employment; housing; medical care; caretaking obligations; social relationships. Even when people are able to post bail, that money would otherwise have paid bills or expenses, setting people back financially for years at a time. And as DA Rollins recognizes, the collateral consequences of criminal records set up barriers that people and their families struggle for the rest of their lives to surmount. As she laid out in The Rollins Memo, a vast body of research supports DA Rollins’ policies for harm reduction and a public health approach, particularly with respect to drug use. On the other hand, O’Keefe’s punitive approach has fueled the opioid crisis rather than prevented deaths in his county. O’Keefe refuses to contend with the mountains of research that DA Rollins has used to inform her policies, and residents of his county will continue to suffer for it. Over-policed and over-prosecuted communities recognize the need for community-led solutions. Effective drug treatment cannot be forced treatment; court-run diversion programs that threaten to punish people when they misstep create harm through conditions that set people up to fail. We must move funding for programs out of the courts and into communities. MYTH: District attorneys don’t have an agenda. O’Keefe writes, “District attorneys should pursue justice for their communities without any predetermined agenda.” But O’Keefe has an agenda: locking up as many Black and Brown people as he can; criminalizing poverty and drug use; ignoring research in order to flaunt a toxic retributivism that does not keep communities safe; and using pre-trial incarceration to coerce pleas. District attorneys emphasize convictions because fear is a powerful motivator for voters and because the entire system would screech to a halt if prosecutors could not force pleas: roughly 97% of all criminal cases end in pleas. District Attorneys decide who to charge with what crimes and whose cases to dismiss. All prosecution is discretionary, and therefore all prosecution is political. MYTH: “The criminal justice system is reactive not proactive. It deals with those who are brought to it.” Many people live in communities where they can go a whole day without seeing a cop car with its lights on. In other places, predominantly poor Black and Brown neighborhoods, people see cop cars and police cameras from their front doorstep. This isn’t by accident. Where police patrol and what they’re looking for is a direct result of policy and intentional distribution of resources, all governed primarily by white law enforcement officials and lawmakers. Government data track arrests, prosecutions, and sentences. We have no way to track actual rates of human behavior. Many people “break the law” every day - but only certain people get labeled criminals, arrested, prosecuted, and sentenced to incarceration when they do so. What is defined as a crime and who is considered a criminal are not natural categories – they’re legal and social constructions. Prosecutors have the capacity to be a check on the racial bias of policing by not prosecuting every case in which someone is summonsed or arrested. Instead what they tend to do is overcharge, request high bails, disparately charge mandatory minimum offenses against people of color, and enhance sentencing to force plea deals and get convictions. The role of the criminal punishment system in our country is to maintain the social and racial order. No matter how much they try to deny their power, prosecutors play a critical role in making sure white wealthy people keep their privilege while people of color and poor people are punished. MYTH: District attorneys do not make laws. They just prosecute people for breaking them, quietly and without fanfare. District attorneys do not do their work silently and leave lawmaking to lawmakers. DAs use their discretion in enforcing the law and also create law by lobbying legislatures. District attorney associations are some of the biggest spenders and loudest voices in criminal law lobbying. DA associations work hard to prevent reform. Advocates sat through hours of testimony by Massachusetts District Attorneys opposing the hugely popular criminal justice reform omnibus bill in 2018. Now conservative DAs are once again using their massive public platform to rail against progressive policies with fear tactics and racist stereotypes. O’Keefe disingenuously asserts that prosecutors quietly do their work without fanfare; voices like his obviously are being heard, in his case in an op-ed published in the Boston Globe which features a picture of him leading a press conference. CONCLUSIONIt is a shame the Boston Globe chose to publish an op-ed riddled with lies and racism - including claims that DA Rollins is unqualified. The time when white male politicians can get away with blaming Black and Brown communities for mass incarceration, and when a major publication glorifies that viewpoint with a spot on its op-ed page, should be over. DA Rollins was elected in a landslide as a qualified lawyer and Black woman who represents her community and her constituents' vision for Suffolk County.

CourtWatchMA stands in solidarity with communities continuing to demand fewer prosecutions and less incarceration. Shame on the Boston Globe for publishing a racist smear with no basis in fact. 3/4/2019 0 Comments The Seventh Week

At the outset, we want to acknowledge that our team is behind in releasing digests. CourtWatch MA is an all-volunteer effort and we are working diligently to make all of our data analysis public as soon as possible. We thank our readers for your patience. And we thank our volunteers for their consistent timeliness and dedication to this collective endeavor.

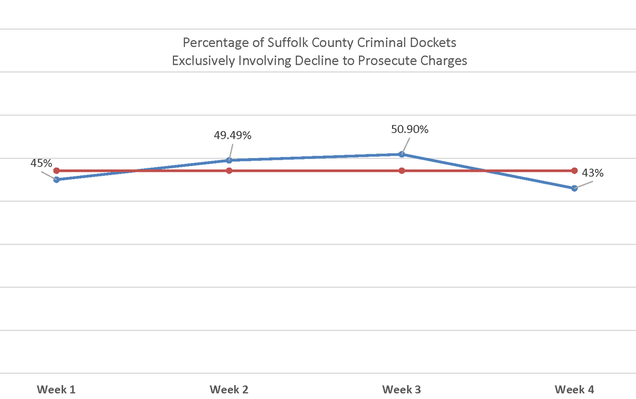

From February 13th to February 19th, courtwatchers observed 162 cases at arraignment across four divisions of Boston Municipal Court (BMC Central, Roxbury, Dorchester, and East Boston).[1] This was our first week with observation in East Boston, though we only had one courtwatcher there on one day. We also note that this week included only four days of observations because of a court holiday. This week, 45.7% of the cases we observed involved only charges that Suffolk County District Attorney Rachael Rollins has pledged to decline to prosecute, either by dismissing at arraignment or diverting through a non-criminal proceeding, program, or outcome. As we’ve seen every week since we began observing, this means almost half the cases we observed this week involved only crimes that District Attorney Rollins identified as low-level, non-violent crimes of poverty, mental illness, and addiction. Our digest again focuses on the data courtwatchers collected about cases that exclusively involved charges from DA Rollins’ Decline to Prosecute list.[2]

Reminder: under the umbrella of cases that DA Rollins pledged to decline to prosecute, we categorize cases that are dismissed outright as dismissals. Cases that are conditionally dismissed – with court costs, community service hours, or a treatment program – and therefore require a subsequent appearance in court are diverted cases. We remain concerned about the impact of imposing conditions which require time, money, or transportation on poor and working class people facing charges.

There were 74 cases involving ONLY charges on the decline to prosecute list this week.

Our dataset this week is smaller than some prior weeks; we do not want to overstate the fact that fewer cases were declined this week by percentage, given how small and variable the datasets are week to week. What we can say, once again, is we still are not seeing significant improvement or substantially more cases being declined. First 100 Days Advocacy Update

|

|

|

Driving Charges (19 total)

|

|

|

Dismissed (without conditions)

|

8

|

42.1%

|

|

Diverted (with conditions)

|

8

|

42.1%

|

|

Released on Personal Recognizance

|

2

|

10.5%

|

|

Warrant issued

|

1

|

5.3%

|

In one driving case this week, a man was charged with unlicensed operation of a motor vehicle. The ADA moved to dismiss with court costs or community service. Judge Sally Kelly denied that ADA request on the grounds that if the DA wants to decline to prosecute they must file a nolle prosequi. The ADA said they had to get DA approval to proceed. Accordingly, the man was released on personal recognizance with a return date for six weeks later. As of today’s date, the case remains an open criminal matter on the trial court electronic case access platform.

We highlight this example for two reasons. First, we know that DA Rollins will likely face resistance from other system actors (judges, probation, police) in enacting her vision; the process of changing the culture of the courts will take persistence, and the sooner her office starts working to reshape customs and practices, the sooner she’ll start reducing harm in individual cases. Second, the absence of a policy memo outlining how an ADA should respond when met with resistance in a case like this meant this man’s case continued as a criminal prosecution; we believe that the existence of a memo and training on office policy could have prevented a situation like this from transpiring. Judges have their own practices, and DA Rollins can prepare ADAs to navigate judges’ preferences. DA Rollins needs a robust policy implementation plan to aid ADAs in making strong recommendations both to decline cases and for release on recognizance in cases where they might formerly have requested cash bail.

For all the charge categories DA Rollins pledged to decline, ADAs should come to arraignment hearings prepared with nolle prosequi statements. This is the only way DA Rollins can ensure consistency in policy across courtrooms; otherwise specific judges may decline ADA motions to dismiss—something we’ve witnessed Judge Kelly do before in separate instances.

We highlight this example for two reasons. First, we know that DA Rollins will likely face resistance from other system actors (judges, probation, police) in enacting her vision; the process of changing the culture of the courts will take persistence, and the sooner her office starts working to reshape customs and practices, the sooner she’ll start reducing harm in individual cases. Second, the absence of a policy memo outlining how an ADA should respond when met with resistance in a case like this meant this man’s case continued as a criminal prosecution; we believe that the existence of a memo and training on office policy could have prevented a situation like this from transpiring. Judges have their own practices, and DA Rollins can prepare ADAs to navigate judges’ preferences. DA Rollins needs a robust policy implementation plan to aid ADAs in making strong recommendations both to decline cases and for release on recognizance in cases where they might formerly have requested cash bail.

For all the charge categories DA Rollins pledged to decline, ADAs should come to arraignment hearings prepared with nolle prosequi statements. This is the only way DA Rollins can ensure consistency in policy across courtrooms; otherwise specific judges may decline ADA motions to dismiss—something we’ve witnessed Judge Kelly do before in separate instances.

What gets diverted?

We categorize any dismissal that included conditions requiring a future court appearance as a diverted case.

This week 13 cases were diverted. Every disposition involved at least one condition, like treatment; a court fee; community service; or probation, despite no findings of fact or guilt. ADAs usually refer to these cases as “conditional dismissals,” but individuals were generally required to report back to court at least once on a future date to prove compliance with the condition. Additional appearances cause stress and strain on individuals and families that could be avoided by outright dismissals.

A majority of the diversions were driving cases – 8 of the 13 (61.5%) cases diverted this week. For driving cases, judges usually gave the person an option of returning with proof of license/registration/insurance, paying a fee between $50 and $200, completing 20 hours community service, or enrolling in driving school.

The other diverted cases were:

This week 13 cases were diverted. Every disposition involved at least one condition, like treatment; a court fee; community service; or probation, despite no findings of fact or guilt. ADAs usually refer to these cases as “conditional dismissals,” but individuals were generally required to report back to court at least once on a future date to prove compliance with the condition. Additional appearances cause stress and strain on individuals and families that could be avoided by outright dismissals.

A majority of the diversions were driving cases – 8 of the 13 (61.5%) cases diverted this week. For driving cases, judges usually gave the person an option of returning with proof of license/registration/insurance, paying a fee between $50 and $200, completing 20 hours community service, or enrolling in driving school.

The other diverted cases were:

|

|

Diverted Cases

(13 total: 8 driving charges, 5 other) |

|

|

Charge(s)

|

Type of Diversion

|

Outcome

|

|

Drug Possession

|

Drug Treatment

|

Treatment at Kelly House

|

|

Drug Possession

|

Mental Health Treatment

|

Physician evaluation

|

|

Trespass

|

Court Condition

|

Stay away from Logan Airport

until next court date |

|

Trespass

|

Court Condition

|

Stay away from Logan Airport

until next court date |

|

Trespass and Shoplifting

|

Court Condition

|

Social services, including shelter

|

We also note that prosecutors continue to rely on punitive conditions that penalize people for being poor, despite DA Rollins’ emphasis during her campaign and recent interviews that she opposes the use of fines and fees to punish people.

Finally, completing community service within the requisite timeframe may mean people need to call out of or cancel work, miss classes, or arrange childcare. Though many judges allow individuals to do community service at a place of their choice, some mandate that individuals serve through the state-run program that requires manual labor and is only offered on certain days.

This kind of community service has no restorative value and is imposed before a person has been convicted of any wrongdoing. Pre-arraignment community service is simply a punishment for being arrested.

Finally, completing community service within the requisite timeframe may mean people need to call out of or cancel work, miss classes, or arrange childcare. Though many judges allow individuals to do community service at a place of their choice, some mandate that individuals serve through the state-run program that requires manual labor and is only offered on certain days.

This kind of community service has no restorative value and is imposed before a person has been convicted of any wrongdoing. Pre-arraignment community service is simply a punishment for being arrested.

Release or Detention Decisions

In 17 cases that advanced as criminal matters, the person being arraigned was released on personal recognizance. In many such cases, the court also imposed conditions—especially common was a stay away or no contact order for the place of the incident or a person involved. Sometimes a person is required to stay away from a shelter where they lived for the last year or a major transit hub through which they have to commute.

In one case of drug possession with intent to distribute, a 25-year-old had been released on an unknown bail amount at the police station. The judge adjusted his release conditions to personal recognizance. The only substance involved: marijuana. Police allegedly found 20-25 bags of marijuana and a scale in his car. DA Rollins speaks about the racial injustice in historical marijuana enforcement, yet her office continues to pursue marijuana cases, including this case of possession with intent to distribute marijuana—a charge she pledged to decline and a legal substance in the state of Massachusetts. Based on DA Rollins’ campaign pledges, this case should not be prosecuted.

In 7 cases exclusively involving charges DA Rollins pledged to decline this week, bail was set. Bail amounts ranged from $100 to $500. Four of these cases involved charges of drug possession and/or possession with intent to distribute and/or resisting arrest. In one of these cases, bail was set on the new charges and bail was revoked on a prior case. The other three cases were charges of larceny under $1200.

In one of these misdemeanor larceny cases, the man being arraigned was homeless and receiving methadone and psychiatric treatment. He already has an outstanding court order for money owed. The ADA recommended $500 bail. The judge imposed $200 bail. A homeless man charged with a crime DA Rollins pledged to decline on a stable treatment regimen was denied access to care and kept in jail because of the actions of a prosecutor who reports to DA Rollins in the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office.

In the remaining 15 cases, we don’t know the final release decision or case outcome because the arraignment was continued—i.e. postponed to a future date or time (7 cases), the person being arraigned remained detained (despite the judge deciding to release them on personal recognizance on the pending charges) in order to resolve a warrant in another court (2 cases), the person did not appear for arraignment and a warrant was issued (5 cases), or the courtwatcher wasn’t sure what happened (1 case).

We again note that people not showing up for arraignment happens rarely, and that courts don’t have to verify that a person actually received a summons before issuing an arrest warrant—a disturbing practice we hope DA Rollins will push to change.

Our data collection on bail may undercount people who have already paid bail at the police station. Courtwatchers have not always been able to reliably document when someone has already posted bail, and in what amount, if they freely walk into court. This is not always explicitly addressed on the record.

Bail is set at the police station by court clerks. How bail amounts are decided is not transparent to the public and bail is set with very little oversight.

In one case of drug possession with intent to distribute, a 25-year-old had been released on an unknown bail amount at the police station. The judge adjusted his release conditions to personal recognizance. The only substance involved: marijuana. Police allegedly found 20-25 bags of marijuana and a scale in his car. DA Rollins speaks about the racial injustice in historical marijuana enforcement, yet her office continues to pursue marijuana cases, including this case of possession with intent to distribute marijuana—a charge she pledged to decline and a legal substance in the state of Massachusetts. Based on DA Rollins’ campaign pledges, this case should not be prosecuted.

In 7 cases exclusively involving charges DA Rollins pledged to decline this week, bail was set. Bail amounts ranged from $100 to $500. Four of these cases involved charges of drug possession and/or possession with intent to distribute and/or resisting arrest. In one of these cases, bail was set on the new charges and bail was revoked on a prior case. The other three cases were charges of larceny under $1200.

In one of these misdemeanor larceny cases, the man being arraigned was homeless and receiving methadone and psychiatric treatment. He already has an outstanding court order for money owed. The ADA recommended $500 bail. The judge imposed $200 bail. A homeless man charged with a crime DA Rollins pledged to decline on a stable treatment regimen was denied access to care and kept in jail because of the actions of a prosecutor who reports to DA Rollins in the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office.

In the remaining 15 cases, we don’t know the final release decision or case outcome because the arraignment was continued—i.e. postponed to a future date or time (7 cases), the person being arraigned remained detained (despite the judge deciding to release them on personal recognizance on the pending charges) in order to resolve a warrant in another court (2 cases), the person did not appear for arraignment and a warrant was issued (5 cases), or the courtwatcher wasn’t sure what happened (1 case).

We again note that people not showing up for arraignment happens rarely, and that courts don’t have to verify that a person actually received a summons before issuing an arrest warrant—a disturbing practice we hope DA Rollins will push to change.

Our data collection on bail may undercount people who have already paid bail at the police station. Courtwatchers have not always been able to reliably document when someone has already posted bail, and in what amount, if they freely walk into court. This is not always explicitly addressed on the record.

Bail is set at the police station by court clerks. How bail amounts are decided is not transparent to the public and bail is set with very little oversight.

The charge breakdowns are as follows [keep in mind that some folks had multiple charges]:

|

Charge

|

Number of Cases

Week 7 |

Total So Far

All 7 Weeks |

|

Trespass

|

21

|

74

|

|

Shoplifting

|

2

|

25

|

|

Larceny under $1200

|

5

|

31

|

|

Disorderly Conduct

|

1

|

18

|

|

Disturbing the Peace

|

(zero)

|

2

|

|

Receiving Stolen Property

|

2

|

12

|

|

Driving Cases (suspended or revoked license or registration)

|

19

|

302

|

|

Breaking and entering for the purpose of shelter

|

(zero)

|

2

|

|

Wanton/Malicious Destruction of Property

|

(zero)

|

10

|

|

Threats (not domestic violence related)

|

3

|

19

|

|

Minor in Possession of Alcohol

|

3

|

3

|

|

Drug Possession

|

17

|

91

|

|

Drug Possession with Intent to Distribute

|

8

|

55

|

|

Resisting Arrest

|

3

|

10

|

In 17 of these cases, the person being arraigned was in jail at the time of arraignment. Among those 17 individuals,

The remaining 8 people were assessed bail (5), had their bail revoked and were assessed bail (1), or were held for transport to another court for an open warrant (2).

In other words, 9 people spent time in jail and ultimately were not prosecuted or were released; they were detained without an ability to shower, change clothes, see their kids, walk their pets, take their medications, or communicate with their jobs or families—only to have a judge determine there was no good reason to detain them.

Further, this means in 52.9% of cases in which a bail magistrate declined to release someone this week, the judge released the individual or diverted or dismissed that person’s case.

While clerks make decisions to set bail at police stations independently of the DA’s office, we hope that District Attorney Rollins will both express her contempt for pre-trial detention and implement a strong policy that avoids pre-trial detention at all costs.

- 6 were released on personal recognizance,

- 2 had their cases diverted, and

- 1 had their case dismissed.

The remaining 8 people were assessed bail (5), had their bail revoked and were assessed bail (1), or were held for transport to another court for an open warrant (2).

In other words, 9 people spent time in jail and ultimately were not prosecuted or were released; they were detained without an ability to shower, change clothes, see their kids, walk their pets, take their medications, or communicate with their jobs or families—only to have a judge determine there was no good reason to detain them.

Further, this means in 52.9% of cases in which a bail magistrate declined to release someone this week, the judge released the individual or diverted or dismissed that person’s case.

While clerks make decisions to set bail at police stations independently of the DA’s office, we hope that District Attorney Rollins will both express her contempt for pre-trial detention and implement a strong policy that avoids pre-trial detention at all costs.

Demographics[3] – Who is Prosecuted for these Offenses?

|

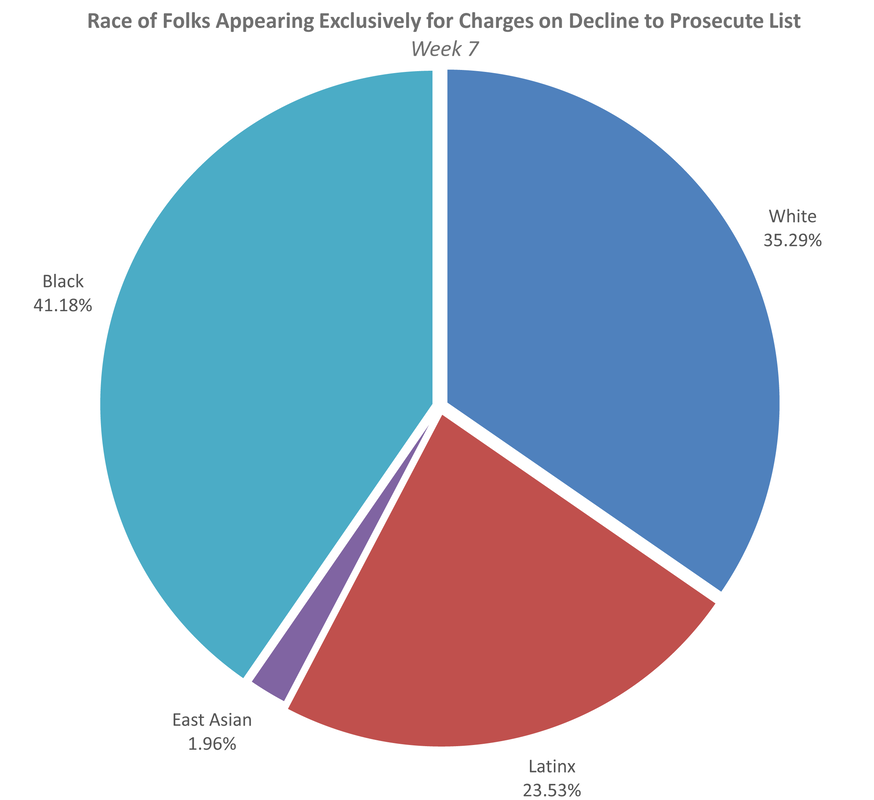

This week courtwatchers observed many cases where the person being arraigned did not appear, and therefore racial demographic observations were impossible. Courtwatchers noted demographics in only 51 of the 74 decline to prosecute cases.

|

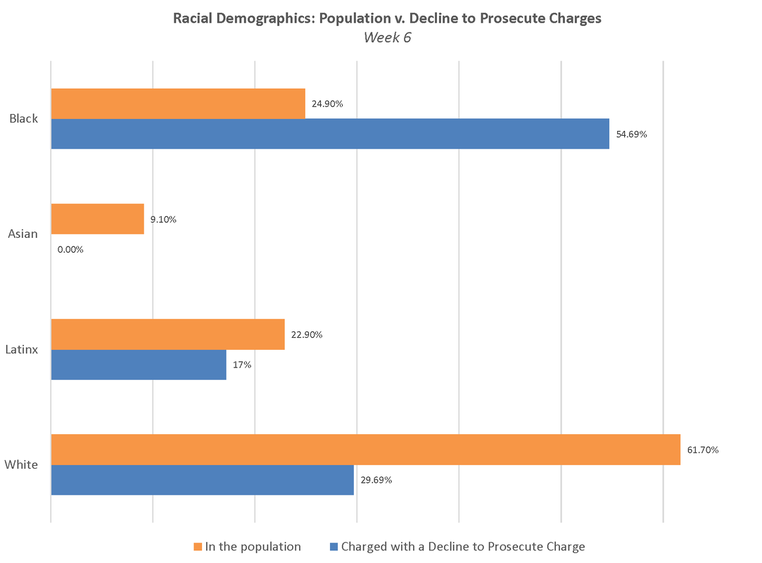

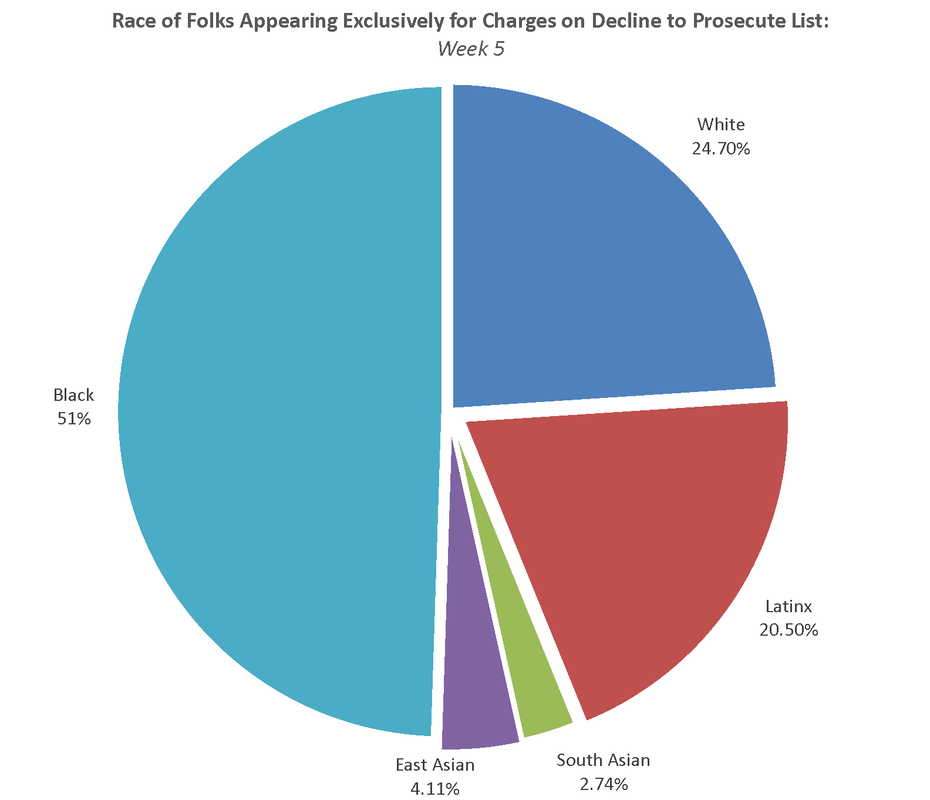

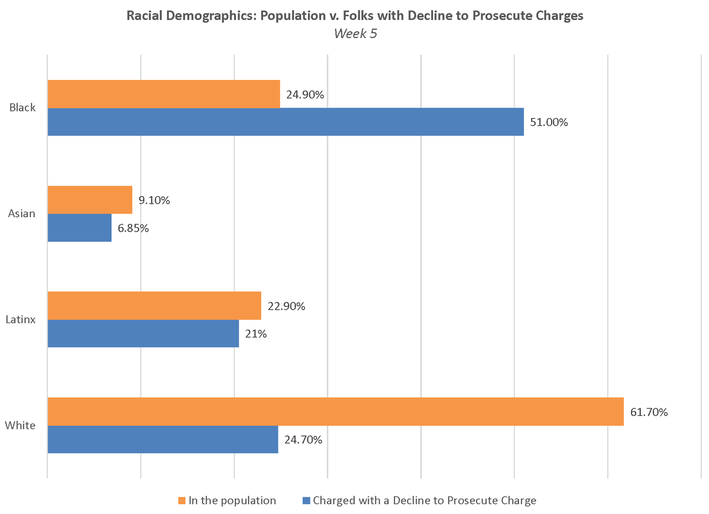

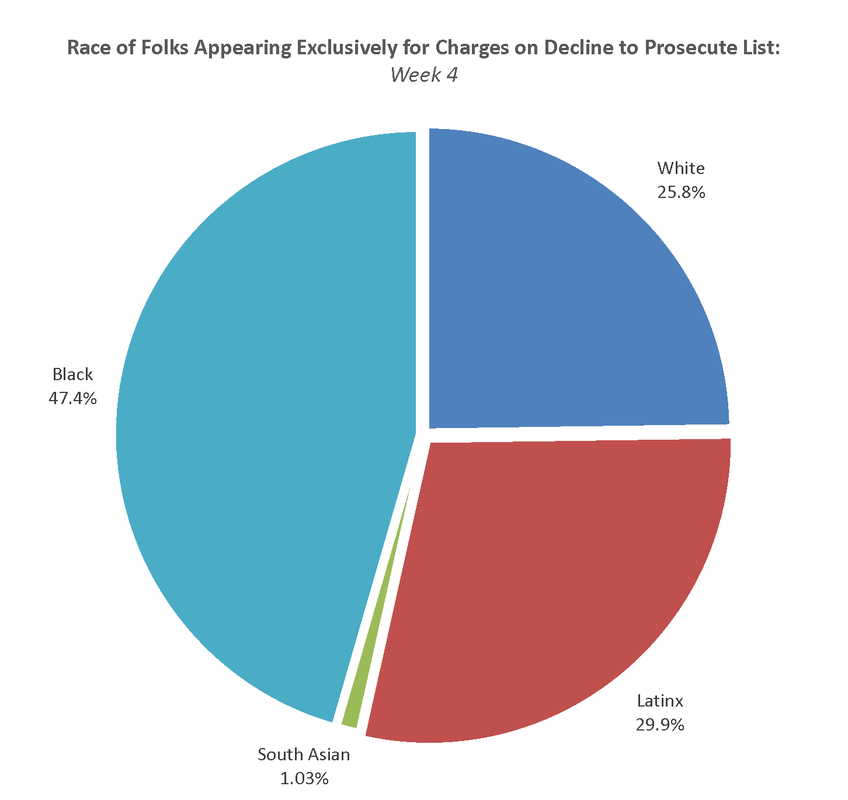

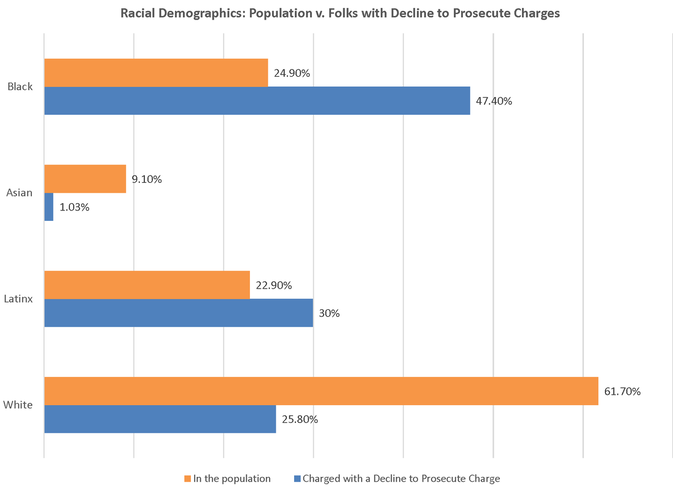

Of the 51 decline to prosecute cases observed this week in which courtwatchers noted demographic information, the racial breakdown of the people arraigned was as follows:

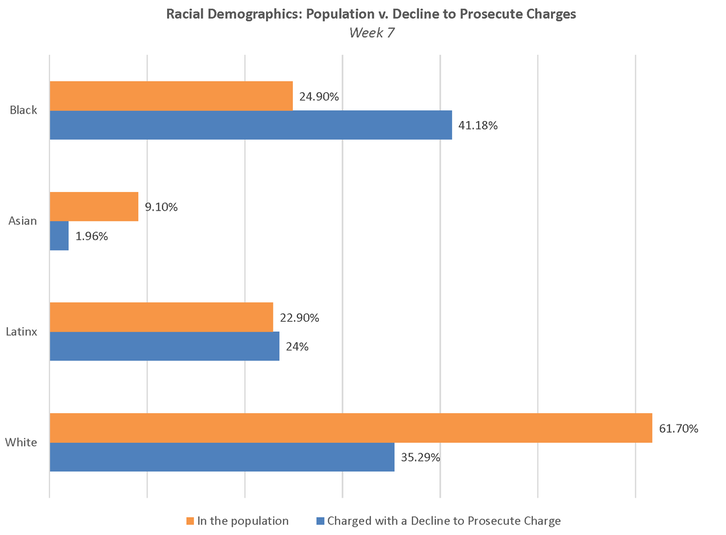

41.18% Black, 23.53% Latinx; 35.29% white, 0% South Asian, and 1.96% East Asian. |

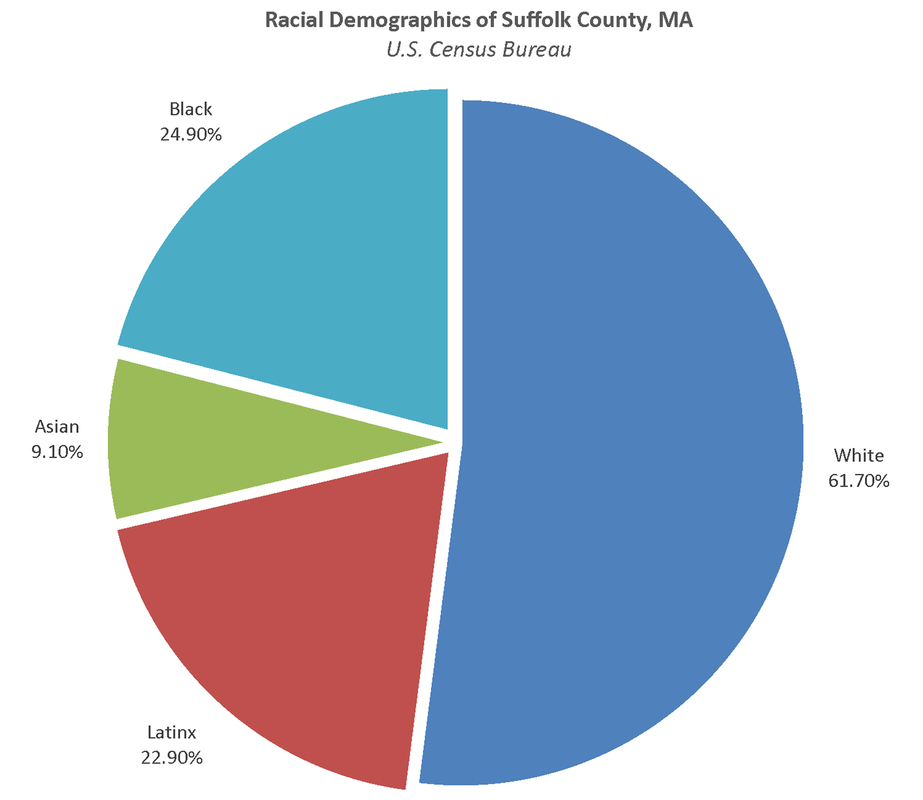

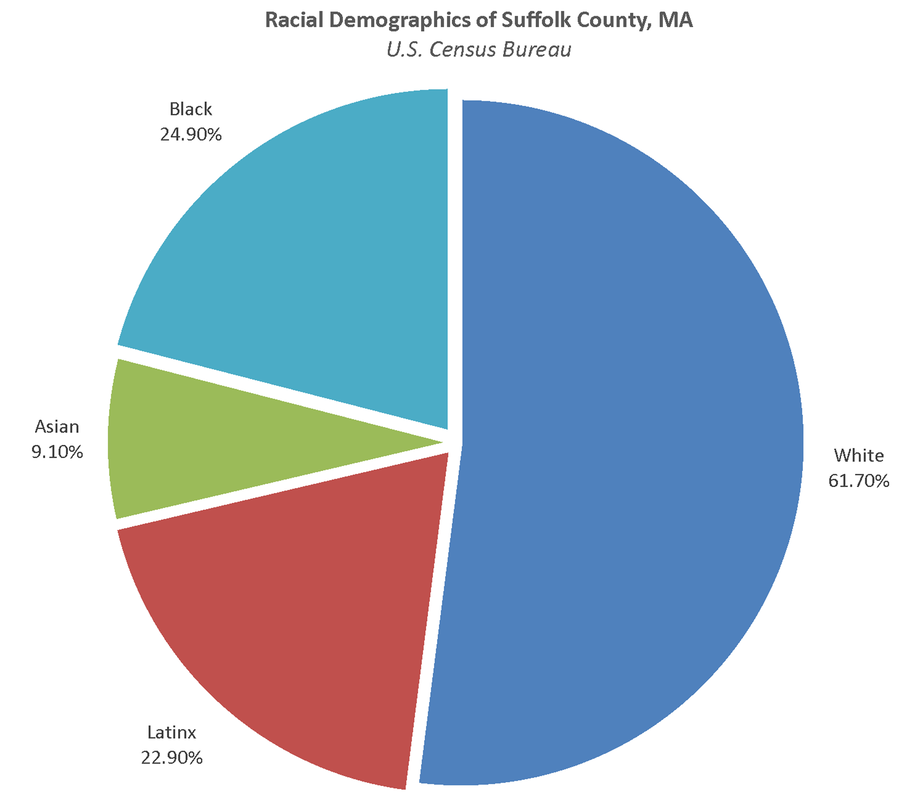

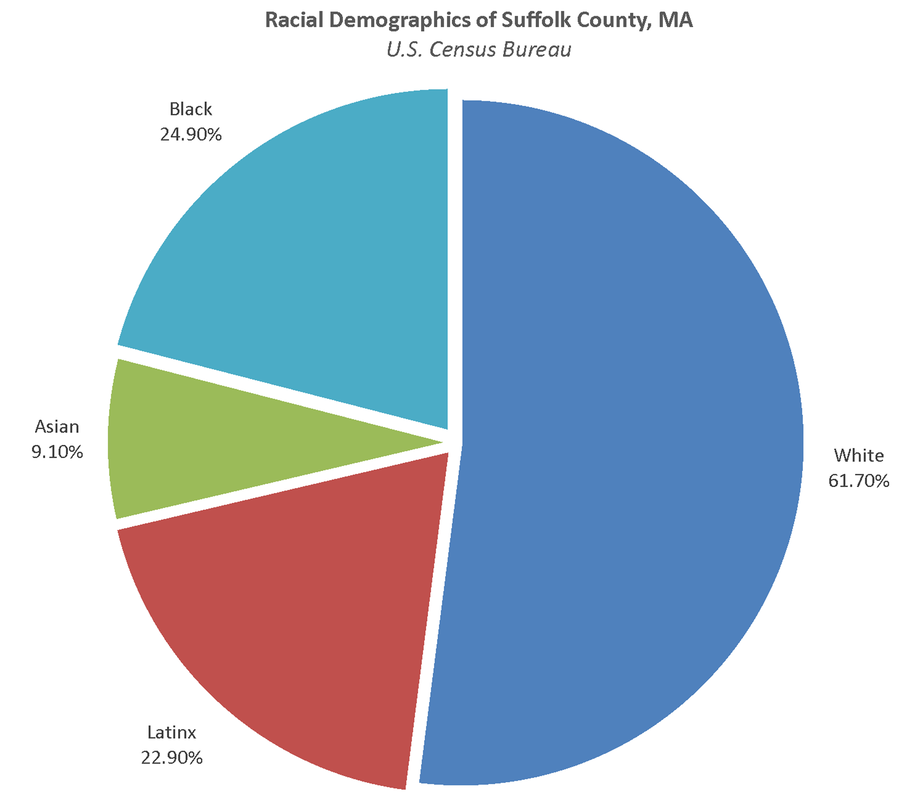

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the demographics of Suffolk County are as follows:

24.9% Black or African American, 22.9% Hispanic of Latino, 61.7% white, 9.1% Asian, 3.4% two or more races, .7% Native American or Alaskan Native, .2% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander |

Black defendants are once again astronomically overrepresented compared to the population, while white defendants are starkly underrepresented.

Other Charges: Beyond the Decline to Prosecute List

Each week we see a number of cases rooted in social or administrative issues that are frequently dismissed and which DA Rollins should consider adding to her pending list of charges to be declined. For example, 5 cases observed this week were for drinking in public, a minor ordinance violation, all of which were dismissed without conditions even when the individual was not present in court.

We hope the forthcoming policy memo includes not only all of the charges DA Rollins identified on the campaign trail but also other petty offenses—including those we have highlighted over the past ten weeks (for example, failure to attend jury duty), in these digests and on twitter.

We hope the forthcoming policy memo includes not only all of the charges DA Rollins identified on the campaign trail but also other petty offenses—including those we have highlighted over the past ten weeks (for example, failure to attend jury duty), in these digests and on twitter.

Snapshot: A Default Removal & ICE

On February 15th, a man appeared in Dorchester to resolve a default. He had been arraigned in July on assault and battery with a dangerous weapon, released on $400 bail. At that July appearance his next court date was scheduled for February 13, 2019. However, he was picked up by ICE at the courthouse and held for the last six months.

Since he was held in immigration detention, he missed court on February 13th. The judge found his failure to appear constituted a default, issued a warrant, and found that the $400 bail he had paid in July should be forfeited.

However, within 2 days of that default, this man came to court on his own with his attorney. He had just been granted asylum, meaning lawful residence in the U.S. on the basis of a credible fear of persecution if returned to his country of origin, and released from ICE custody. The judge acknowledged that no one knew he had been in ICE custody. The default was cleared; bail was reinstated; his next court date was scheduled for April.

We tell this story for a few reasons. For one thing, this man’s case illustrates that so-called “failures to appear” may not reflect willful avoidance of court obligations; often, we see people with explainable impediments to showing up to court—for example, they were detained elsewhere; they lacked transportation to court; they face housing insecurity and never received a summons on the underlying charge. And yet defaults are used to enhance criminal consequences: a default on one’s record often encourages judges to set a higher bail or to issue a warrant when someone misses court in the future. The court system does not track data to determine how many “failures to appear” reflect actual “flight,” and yet the failure to appear boogeyman continues to take up an undue amount of space in ongoing conversations about bail reform—despite the fact that the failure to appear rate in Massachusetts is exceedingly low even with this confounded data.

Second, we tell this story because of what it says about how our court system and state and local law enforcement continue to allow ICE to trample the rights of immigrants. This man was picked up at the courthouse. He was secreted away to detention without notifying the court system. He was not brought in for his next court appearance. ICE expects cooperation from our courts and law enforcement, meanwhile ICE denies immigrants the opportunity to vindicate their rights in court, prevents them from meaningful participation in their defense in pending criminal cases, and puts them in jeopardy of further heightened criminal penalties. DA Rollins promised to implement an ICE security policy within 30 days of taking office. Recent reporting demonstrates that the Boston Police Department continues to work collusively with ICE. Where is DA Rollins’ promised leadership to protect sanctuary in Suffolk County?

Since he was held in immigration detention, he missed court on February 13th. The judge found his failure to appear constituted a default, issued a warrant, and found that the $400 bail he had paid in July should be forfeited.

However, within 2 days of that default, this man came to court on his own with his attorney. He had just been granted asylum, meaning lawful residence in the U.S. on the basis of a credible fear of persecution if returned to his country of origin, and released from ICE custody. The judge acknowledged that no one knew he had been in ICE custody. The default was cleared; bail was reinstated; his next court date was scheduled for April.

We tell this story for a few reasons. For one thing, this man’s case illustrates that so-called “failures to appear” may not reflect willful avoidance of court obligations; often, we see people with explainable impediments to showing up to court—for example, they were detained elsewhere; they lacked transportation to court; they face housing insecurity and never received a summons on the underlying charge. And yet defaults are used to enhance criminal consequences: a default on one’s record often encourages judges to set a higher bail or to issue a warrant when someone misses court in the future. The court system does not track data to determine how many “failures to appear” reflect actual “flight,” and yet the failure to appear boogeyman continues to take up an undue amount of space in ongoing conversations about bail reform—despite the fact that the failure to appear rate in Massachusetts is exceedingly low even with this confounded data.

Second, we tell this story because of what it says about how our court system and state and local law enforcement continue to allow ICE to trample the rights of immigrants. This man was picked up at the courthouse. He was secreted away to detention without notifying the court system. He was not brought in for his next court appearance. ICE expects cooperation from our courts and law enforcement, meanwhile ICE denies immigrants the opportunity to vindicate their rights in court, prevents them from meaningful participation in their defense in pending criminal cases, and puts them in jeopardy of further heightened criminal penalties. DA Rollins promised to implement an ICE security policy within 30 days of taking office. Recent reporting demonstrates that the Boston Police Department continues to work collusively with ICE. Where is DA Rollins’ promised leadership to protect sanctuary in Suffolk County?

Cause for Concern: Practices to Change

As stated above, 39 cases involving only charges to be declined were not dismissed or diverted. Those cases should also be declined, and we hope that this will change in the weeks to come.

Courtwatchers observed 6 cases involving charges from the decline to prosecute list in which an ADA asked for bail. We again emphasize that ADAs should always recommend release on personal recognizance in cases when the person is not a flight risk and should never request bail for charges on the do not prosecute list.

Courtwatchers documented 10 cases this week involving charges from the decline to prosecute list in which ADAs asked for conditions instead of dismissing the case outright. Further, courtwatchers documented 17 decline to prosecute cases in which ADAs asked for release on personal recognizance—intentionally continuing the case as a criminal matter.

Finally, we saw 1 case in which an ADA successfully requested that bail on a prior case be revoked for a person facing new charges of drug possession and resisting arrest, in addition to requesting bail on the new charges. Because his bail was revoked, this man will now be held for 60 days without the possibility of release. DA Rollins should monitor this practice among her ADAs and prevent this from happening again. Just as we advocate that bail should never be set on a charge to be declined, bail should likewise never be revoked in connection with a docket involving this set of charges.

In all cases, we hope ADAs seek the least burdensome outcome that will resolve the case. For all 15 charges DA Rollins has identified, we believe cases should generally be dismissed without conditions.

Courtwatchers observed 6 cases involving charges from the decline to prosecute list in which an ADA asked for bail. We again emphasize that ADAs should always recommend release on personal recognizance in cases when the person is not a flight risk and should never request bail for charges on the do not prosecute list.

Courtwatchers documented 10 cases this week involving charges from the decline to prosecute list in which ADAs asked for conditions instead of dismissing the case outright. Further, courtwatchers documented 17 decline to prosecute cases in which ADAs asked for release on personal recognizance—intentionally continuing the case as a criminal matter.

Finally, we saw 1 case in which an ADA successfully requested that bail on a prior case be revoked for a person facing new charges of drug possession and resisting arrest, in addition to requesting bail on the new charges. Because his bail was revoked, this man will now be held for 60 days without the possibility of release. DA Rollins should monitor this practice among her ADAs and prevent this from happening again. Just as we advocate that bail should never be set on a charge to be declined, bail should likewise never be revoked in connection with a docket involving this set of charges.

In all cases, we hope ADAs seek the least burdensome outcome that will resolve the case. For all 15 charges DA Rollins has identified, we believe cases should generally be dismissed without conditions.

Policy: Procedural Change, But No Substantive Policies

On March 11th, DA Rollins announced her first policy change to implement a campaign promise: the creation of a four-person independent review committee for a police-involved shooting. The Discharge Integrity Team (“DIT”) will meet on a monthly basis with DA Rollins and her First Assistant to review the progress of her Office’s investigation of a specific incident—a February 22nd shooting between 36-year-old Kasim Kahrim and Boston Police officers, in which Mr. Kahrim was killed and an officer suffered multiple gunshot wounds. The SCDAO press release stated the four appointed individuals would “assess the state of the evidence, monitor the direction of the investigation, and examine the procedural steps undertaken by investigators on the ground.” This outside review team aims to fulfill Rollins’ campaign promise to “remove the investigative process from the ADAs in the Office and have a select group of external experts handle these investigations and report the finding directly to the DA.”

We applaud DA Rollins for delivering on this campaign pledge and implementing a significant procedural change that will act as an accountability check on SCDAO investigations of officer-involved shootings and provide an oversight mechanism when police use force. Local organizers, in particular survivors of loved ones murdered by police, have sought this change for years. We hope this is the first of many steps DA Rollins takes to be responsive to the needs of the community she represents.

However, to date, DA Rollins has not delivered on many of the core components of her substantive policy platform: an ICE security policy within 30 days of taking office; policy on declining charges that criminalize poverty, addiction, and mental illness; bail reform—in particular, “eliminating cash bail for individuals who do not pose a flight risk.”

We have long passed DA Rollins’ own benchmark of six weeks, the time it took DA Larry Krasner in Philadelphia to issue his first policy memo. DA Rollins continues to speak publicly about the list of offenses she pledged to decline, her intent to implement policy, and her promise to review the policy and internal data after six months to see what is working. We appreciate her continued commitment to these goals—but each day that goes by without formal policy, the harms she rightly identified continue.

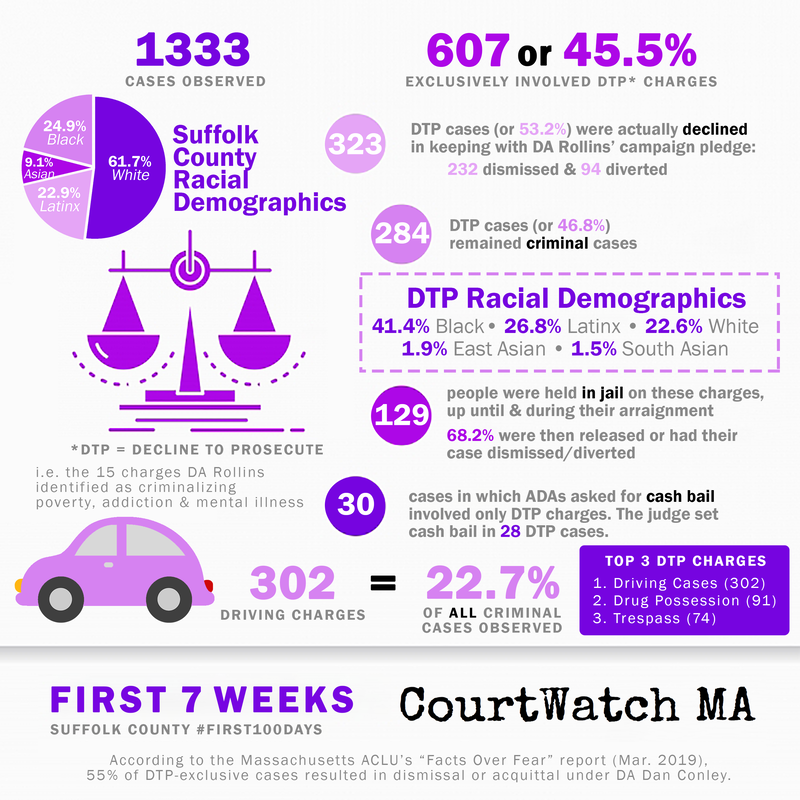

In a report released on March 19th, the ACLU of Massachusetts analyzed two years of criminal prosecution data from the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office under DA Rollins’ predecessor, Dan Conley. Data like this has never been released to the public in Suffolk County. The report found, among other things:

The ACLU analyzed dismissals and acquittals across the life of criminal cases, not only dismissals at arraignments. Therefore their findings are not a perfect comparator or baseline against which to measure our findings and the progress of the Rollins administration. Still, this snapshot demonstrates that DA Rollins has not improved upon her predecessor’s record when it comes to these minor offenses. In these weekly digests, we’ve published data analysis based on data collected by volunteers that mirrors the dismissal rate and racial disparities seen in the data from 2013-2014.

DA offices can be the drivers of community-led change, rather than subordinate to the forces of other institutional actors. We amplify the ACLU’s recommendations, which echo our longstanding advocacy points; DA Rollins should:

We applaud DA Rollins for delivering on this campaign pledge and implementing a significant procedural change that will act as an accountability check on SCDAO investigations of officer-involved shootings and provide an oversight mechanism when police use force. Local organizers, in particular survivors of loved ones murdered by police, have sought this change for years. We hope this is the first of many steps DA Rollins takes to be responsive to the needs of the community she represents.

However, to date, DA Rollins has not delivered on many of the core components of her substantive policy platform: an ICE security policy within 30 days of taking office; policy on declining charges that criminalize poverty, addiction, and mental illness; bail reform—in particular, “eliminating cash bail for individuals who do not pose a flight risk.”

We have long passed DA Rollins’ own benchmark of six weeks, the time it took DA Larry Krasner in Philadelphia to issue his first policy memo. DA Rollins continues to speak publicly about the list of offenses she pledged to decline, her intent to implement policy, and her promise to review the policy and internal data after six months to see what is working. We appreciate her continued commitment to these goals—but each day that goes by without formal policy, the harms she rightly identified continue.

In a report released on March 19th, the ACLU of Massachusetts analyzed two years of criminal prosecution data from the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office under DA Rollins’ predecessor, Dan Conley. Data like this has never been released to the public in Suffolk County. The report found, among other things:

- Black people in Suffolk County were disproportionately charged with “Decline to Prosecute” offenses.

- Over the two-year period, Black people were three times more likely to be charged with trespass or resisting arrest than white people, and four times more likely to be charged with a motor vehicle offense—in one neighborhood, 15 times more likely.

- Black people were not only charged at higher rates: in many of the “Decline to Prosecute” categories, Black people were more likely to face an adverse disposition (e.g., admission to sufficient fact or conviction with a term of probation or incarceration).

- During that two-year period, the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office prosecuted 55% of DTP cases to a non-adverse disposition. In other words, over half of the DTP cases prosecuted between 2013 and 2014 resulted in dismissals or acquittals.

- Even though a majority of these cases ultimately resolved without a criminal conviction or adverse finding, people often had to go through many months of pre-trial hearings before their cases were dismissed, which causes stress and strain particularly if people were incarcerated and/or low-income, hourly workers, and/or homeless.

The ACLU analyzed dismissals and acquittals across the life of criminal cases, not only dismissals at arraignments. Therefore their findings are not a perfect comparator or baseline against which to measure our findings and the progress of the Rollins administration. Still, this snapshot demonstrates that DA Rollins has not improved upon her predecessor’s record when it comes to these minor offenses. In these weekly digests, we’ve published data analysis based on data collected by volunteers that mirrors the dismissal rate and racial disparities seen in the data from 2013-2014.

DA offices can be the drivers of community-led change, rather than subordinate to the forces of other institutional actors. We amplify the ACLU’s recommendations, which echo our longstanding advocacy points; DA Rollins should:

- “fully implement her promised ‘Decline to Prosecute’ policy. She must honor her campaign platform of presumptive non-prosecution of the 15 misdemeanors and low-level felonies.”

- “improve record-keeping and data collection.” The ACLU further recommends, “Prosecution statistics should be analyzed and reported out on a week-to-week basis. Data should include but not be limited to prosecution statistics for each court, status of each case and next court date, bail requests, charge breakdowns, plea offers, final disposition, as well as race and ethnicity data. This will ensure that DTP charges are being dismissed, and help identify trends, problems, and costs of prosecution.”

- “work with Suffolk County residents, community organizers, health care advocates, drug treatment specialists, anti-poverty activists, local small business owners, youth and youth workers, and others to develop a robust network of community-led alternatives to prosecution.”

We know that DA Rollins has met with a coalition of community groups working in these domains and her office has been provided with additional names, but there has been limited follow-up to advance community-led alternatives.

- “work with the Boston Police Department, the Massachusetts State Police, and all other municipal and university law enforcement agencies in Suffolk County to ensure that people are not being charged unnecessarily or in a racially disparate manner.”

Takeaways: Reactions from the CourtWatch MA team

We are publishing this digest late. We are now well into week 11 without substantive office policy. The charges DA Rollins pledged to decline continue to be criminally prosecuted; people continue to be held on cash bail in response to ADA requests; and the only data we have is the data our volunteers collect.

All told, Suffolk County’s district courts continue to churn through minor cases and disrupt people’s lives with time in jail, punitive conditions, and unnecessary arrest warrants for court absences.

We have now published seven weeks of data analysis. As of our date of publication, DA Rollins has already been in office for eleven weeks. Her first quarterly Town Hall is next week. We hope she will take some time to address our continuing advocacy points:

We’re waiting. And we’ll be watching.

All told, Suffolk County’s district courts continue to churn through minor cases and disrupt people’s lives with time in jail, punitive conditions, and unnecessary arrest warrants for court absences.

We have now published seven weeks of data analysis. As of our date of publication, DA Rollins has already been in office for eleven weeks. Her first quarterly Town Hall is next week. We hope she will take some time to address our continuing advocacy points:

- Publish SCDAO data;

- Issue policy on core substantive campaign pledges (ICE, bail, and charges to decline); and

- Train ADAs on substantive policy changes and hold them accountable if they deviate from office policy.

We’re waiting. And we’ll be watching.

[1] This week we again removed cases from our dataset representing status hearings, diversion check ins, restraining orders, probation violations, or other types of hearings that were not initial arraignments. We again note that the total number of hearings observed is not the total number of arraignments which transpired in those courts. For a more comprehensive count of arraignments, you can view sparse information about all criminal cases, by court and date of filing, at masscourts.org. Select the court, use the “case type” tab, select the relevant date(s), and select both “criminal” and “criminal cross site” as the case type. For the same period (February 13th to February 19th), a search on MassCourts reveals 116 cases out of BMC Central, 55 cases out of Roxbury, 67 cases out of Dorchester, and 23 cases out of East Boston, for a total of 261 cases filed this week in these courts. We note that this number also does not reflect the total number of cases arraigned in these courts; courtwatchers also observe arraignments of older dockets with some frequency.

[2] Because of limited capacity of the CourtWatch MA team, we again did not verify every case against the limited available charge information on masscourts.org. We have verified the charge in any case where the courtwatcher left the charge blank, did not hear the charge, or noted that reading the charge was waived in court. It is of course possible courtwatchers misheard the charge(s) in any given case; we reiterate that our data collection is not a substitute for open government. We remain cautiously optimistic that District Attorney Rollins will release data tracked by the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office going forward, as she pledged during her campaign.

[3] Courtwatchers write down demographic information (age, race, gender) based on observation alone; we recognize that this is an imperfect way to determine markers of identity. We ask courtwatchers to note this information because (1) courts are unlikely to disclose this information even if we requested every docket; and (2) the system operates based on an individual’s outward perception and expression, regardless of their stated identity, so demographic observations are a reasonable methodology for this particular project. We again reiterate that courtwatchers can select as many racial demographic markers as apply.

[2] Because of limited capacity of the CourtWatch MA team, we again did not verify every case against the limited available charge information on masscourts.org. We have verified the charge in any case where the courtwatcher left the charge blank, did not hear the charge, or noted that reading the charge was waived in court. It is of course possible courtwatchers misheard the charge(s) in any given case; we reiterate that our data collection is not a substitute for open government. We remain cautiously optimistic that District Attorney Rollins will release data tracked by the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office going forward, as she pledged during her campaign.

[3] Courtwatchers write down demographic information (age, race, gender) based on observation alone; we recognize that this is an imperfect way to determine markers of identity. We ask courtwatchers to note this information because (1) courts are unlikely to disclose this information even if we requested every docket; and (2) the system operates based on an individual’s outward perception and expression, regardless of their stated identity, so demographic observations are a reasonable methodology for this particular project. We again reiterate that courtwatchers can select as many racial demographic markers as apply.

3/1/2019 0 Comments

The Sixth Week

At the outset, we want to acknowledge that our team is behind in releasing digests. CourtWatch MA is an all-volunteer effort and we are working diligently to make all of our data analysis public as soon as possible.

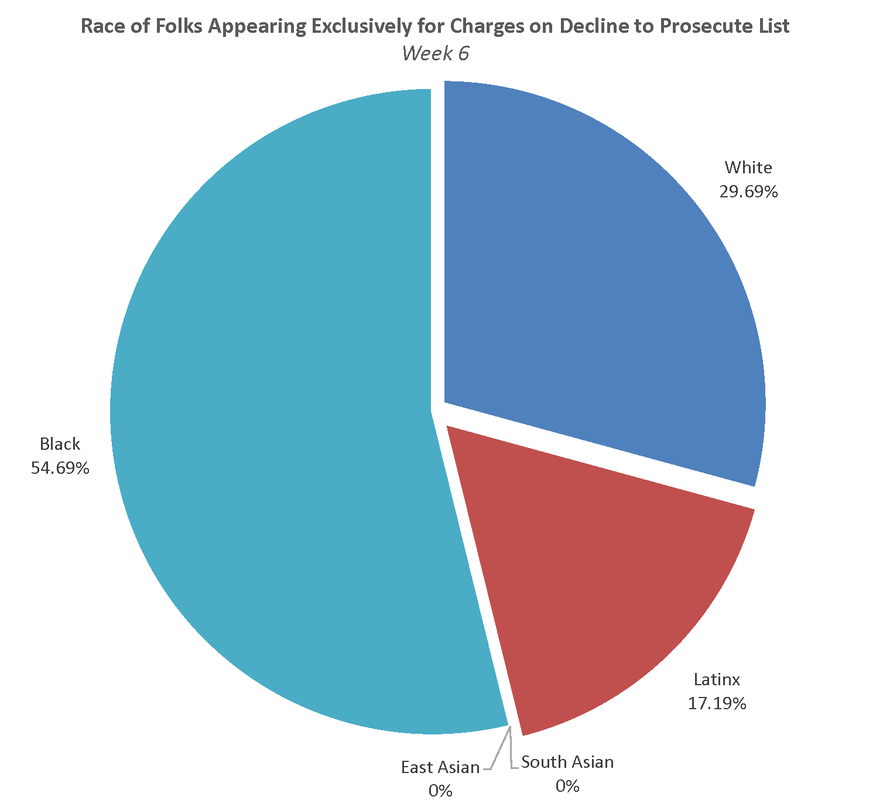

From February 6th to February 12th, our courtwatchers observed 201 cases at arraignment across three divisions of Boston Municipal Court (BMC Central, Roxbury, and Dorchester).[1]

This week, 44.8% of the cases we observed involved only charges that Suffolk County District Attorney Rachael Rollins has pledged to decline to prosecute, either by dismissing at arraignment or diverting through a non-criminal proceeding, program, or outcome. As we’ve seen every week since we began observing, this means almost half the cases we observed this week involved only crimes that District Attorney Rollins has identified as low-level, non-violent crimes rooted in poverty, mental illness, and addiction.

Our digest again focuses on the data courtwatchers collected about cases that exclusively involved charges from DA Rollins’ Decline to Prosecute list.[2]

From February 6th to February 12th, our courtwatchers observed 201 cases at arraignment across three divisions of Boston Municipal Court (BMC Central, Roxbury, and Dorchester).[1]

This week, 44.8% of the cases we observed involved only charges that Suffolk County District Attorney Rachael Rollins has pledged to decline to prosecute, either by dismissing at arraignment or diverting through a non-criminal proceeding, program, or outcome. As we’ve seen every week since we began observing, this means almost half the cases we observed this week involved only crimes that District Attorney Rollins has identified as low-level, non-violent crimes rooted in poverty, mental illness, and addiction.

Our digest again focuses on the data courtwatchers collected about cases that exclusively involved charges from DA Rollins’ Decline to Prosecute list.[2]

Reminder: under the umbrella of cases that DA Rollins pledged to decline to prosecute, we categorize cases that are dismissed outright as dismissals. Cases that are conditionally dismissed – with court costs, community service hours, or a treatment program – and therefore require a subsequent appearance in court are diverted cases. We remain concerned about the impact of imposing conditions which require time, money, or transportation on poor and working class people facing charges.

There were 90 cases involving ONLY charges on the decline to prosecute list this week.

After six weeks of monitoring and analysis in three BMC courts, we again see that DA Rollins has not made significant strides to progressively implement her list of charges to be declined.

We want DA Rollins to succeed in implementing her bold campaign pledge to decline to prosecute these minor offenses that comprise almost half of all criminal court dockets every week in the BMC courts where we observe.

Our First 100 Days project aims to hold her accountable precisely because we are excited at the prospect of transformation for our courts and our communities. More than 60 days into her administration, we remain concerned about when policies will be issued and implemented.

Both in the press and in meetings with community members, DA Rollins’ office continues to promise that much-anticipated changes are coming. Compared to the rollout of policy by her peers—whether Larry Krasner in Philadelphia, Wesley Bell in St. Louis, or Andrea Harrington in Berkshire County, MA—DA Rollins has fallen behind.

We are more than halfway through the First 100 Days. Her office remains without policy, even though DA Rollins has spoken publicly about the fact that as a District Attorney she is not hampered by any legislative body and can act swiftly as an executive to enact her vision.

- 42.2% of these cases (38 cases) advanced as criminal matters.

- 38 of these cases were dismissed at arraignment.

- 14 of these cases were diverted at arraignment

- Therefore, a total of 52 cases, or roughly 57.7%, were declined within the meaning of DA Rollins’ campaign pledge.

After six weeks of monitoring and analysis in three BMC courts, we again see that DA Rollins has not made significant strides to progressively implement her list of charges to be declined.

We want DA Rollins to succeed in implementing her bold campaign pledge to decline to prosecute these minor offenses that comprise almost half of all criminal court dockets every week in the BMC courts where we observe.

Our First 100 Days project aims to hold her accountable precisely because we are excited at the prospect of transformation for our courts and our communities. More than 60 days into her administration, we remain concerned about when policies will be issued and implemented.

Both in the press and in meetings with community members, DA Rollins’ office continues to promise that much-anticipated changes are coming. Compared to the rollout of policy by her peers—whether Larry Krasner in Philadelphia, Wesley Bell in St. Louis, or Andrea Harrington in Berkshire County, MA—DA Rollins has fallen behind.

We are more than halfway through the First 100 Days. Her office remains without policy, even though DA Rollins has spoken publicly about the fact that as a District Attorney she is not hampered by any legislative body and can act swiftly as an executive to enact her vision.

What gets dismissed?

For the sixth week in a row, the majority of dismissals were driving cases – 23 of the 38 cases (60.5%) that were dismissed. The other 15 cases dismissed at arraignment were incidents of trespass (9), shoplifting (1), disorderly conduct (2), wanton or malicious destruction of property (1), and drug possession (2).

In 3 of these dismissed cases, the person had spent time in jail, only to subsequently have their case dismissed entirely:

As we discussed at length last week, while it’s appropriate that these cases were dropped, any time spent in detention is harmful. ADAs should stop bringing these charges altogether, or at the very least, ask that judges dismiss these cases outright.

Over the past six weeks we have seen very few outright dismissals for most of the charges on DA Rollins’ list. Even when a handful of cases involving drug possession or trespass or shoplifting charges were dismissed, usually many more of those charges remained criminal cases. For example, this week only 2 out of 15 possession charges were dismissed and 2 were diverted. That means 73.3% of this week’s possession cases proceeded as criminal matters.

Years of public health research has confirmed that “[t]he risk of overdose death after release from correctional facilities has been shown to be more than 10 times the risk in the general population.” And yet the police have the most resistance to dismissing possession and possession with intent to distribute cases, which besides driving offenses are also among the most populous charge categories on DA Rollins’ list to decline. These decisions are especially important to shifting the punitive culture of the courts. Abundant public health research identifies the risks and costs of trying to prosecute our way out of the opioid crisis, and DAs who chose to follow science instead of fear-mongering have seen dramatic, life-saving results.

A majority of driving cases (73.2%) were declined this week at arraignment. Undocumented people are particularly vulnerable when arrested and arraigned on driving charges. It is our hope that declining to prosecute all driving charges will disincentive arrest so driving matters can be handled civilly like they are in many predominantly white suburbs.

In 3 of these dismissed cases, the person had spent time in jail, only to subsequently have their case dismissed entirely:

- In a trespass case, the man being arraigned had a default on the charge from January, but still the ADA asked for a dismissal conditioned on eight community service hours already completed. The judge dismissed in view of that prior service and without further conditions, but specified that the dismissal was post-arraignment because this person has a history of multiple trespass charges. A post-arraignment dismissal means charges will appear on a person’s records and they will have to answer ‘yes’ if they are ever asked if they have been charged with a crime.

- In a shoplifting case, the ADA asked for release on personal recognizance, but the judge dismissed it outright.

- In a drug possession case, the young Black man being arraigned had been enrolled in detox and the Salvation Army treatment program, but had a seizure while there and was transferred to a hospital for care. He was taken into custody because probation did not realize that he had entered into the treatment program. The ADA asked to dismiss pre-arraignment, which the judge approved.

As we discussed at length last week, while it’s appropriate that these cases were dropped, any time spent in detention is harmful. ADAs should stop bringing these charges altogether, or at the very least, ask that judges dismiss these cases outright.

Over the past six weeks we have seen very few outright dismissals for most of the charges on DA Rollins’ list. Even when a handful of cases involving drug possession or trespass or shoplifting charges were dismissed, usually many more of those charges remained criminal cases. For example, this week only 2 out of 15 possession charges were dismissed and 2 were diverted. That means 73.3% of this week’s possession cases proceeded as criminal matters.

Years of public health research has confirmed that “[t]he risk of overdose death after release from correctional facilities has been shown to be more than 10 times the risk in the general population.” And yet the police have the most resistance to dismissing possession and possession with intent to distribute cases, which besides driving offenses are also among the most populous charge categories on DA Rollins’ list to decline. These decisions are especially important to shifting the punitive culture of the courts. Abundant public health research identifies the risks and costs of trying to prosecute our way out of the opioid crisis, and DAs who chose to follow science instead of fear-mongering have seen dramatic, life-saving results.

A majority of driving cases (73.2%) were declined this week at arraignment. Undocumented people are particularly vulnerable when arrested and arraigned on driving charges. It is our hope that declining to prosecute all driving charges will disincentive arrest so driving matters can be handled civilly like they are in many predominantly white suburbs.

|

|

Driving Charges (41 total)

|

|

|

Dismissed (without conditions)

|

23

|

56.1%

|

|

Diverted (with conditions)

|

7

|

17.1%

|

|

Released on Personal Recognizance

|

5

|

12.2%

|

|

Other Outcome

(arraignment continued, warrant issued, cash bail, outcome unknown) |

6

|

14.6%

|

What gets diverted?

We categorize any dismissal that included conditions requiring a future court appearance as a diverted case in an effort to more accurately represent the data we collect.

This week 14 cases were diverted. Every disposition involved at least one condition, like treatment; a court fee; community service; or probation. ADAs usually refer to these cases as “conditional dismissals,” but individuals were generally required to report back to court at least once on a future date to prove compliance with the condition. Additional appearances cause stress and strain on families that could be avoided by outright dismissals.

Much like dismissals, half of the diversions were driving cases – 7 of the 14 (50%) cases diverted this week. For driving cases, judges usually gave the person an option of returning with proof of license/registration/insurance, paying a fee between $50 and $150, completing community service, or enrolling in driving school.

This week 14 cases were diverted. Every disposition involved at least one condition, like treatment; a court fee; community service; or probation. ADAs usually refer to these cases as “conditional dismissals,” but individuals were generally required to report back to court at least once on a future date to prove compliance with the condition. Additional appearances cause stress and strain on families that could be avoided by outright dismissals.

Much like dismissals, half of the diversions were driving cases – 7 of the 14 (50%) cases diverted this week. For driving cases, judges usually gave the person an option of returning with proof of license/registration/insurance, paying a fee between $50 and $150, completing community service, or enrolling in driving school.

The other diverted cases were:

|

|

Diverted Cases

(14 total: 7 driving charges, 7 other) |

|

|

Charge(s)

|

Type of Diversion

|

Outcome

|

|

Larceny under $1200

|

Court Costs

|

$150

|

|

Shoplifting

|

Court Costs

|

$150

|

|

Disorderly Conduct

|

Court Costs

|

$150

|

|

Trespass, Wanton/Malicious Destruction of Property, and Drug Possession

|

Community Service

|

18 hours

|

|

Larceny under $1200

|

Probation

|

Evaluation for 276A diversion

|

|

Drug Possession

|

Community Service

|

10 hours

|

|

Trespass

|

Community Service

|

10 hours

|

The case of larceny under $1200 which was referred to probation for a diversion evaluation was charged against a 20-year-old high school student. A legislative Task Force is currently evaluating raising the age of juvenile court jurisdiction to include emerging adults ages 18 to 20, consistent with a vast body of neuroscience research about brain development among juveniles and young adults. Especially because this individual is so young and should be encouraged to focus on school, additional conditions and obligations may do more harm than good. DA Rollins should reconsider whether diversion is truly preferable to dismissal in all cases, but especially a case like this.

We also note that, though DA Rollins emphasized during her campaign the need to get people access to services, not hand down sentences, we often see punitive conditions (court costs and community service hours) to address what DA Rollins has identified as root causes in many cases like these: poverty, addiction, and mental illness. Especially in theft cases, where poverty or addiction may be a primary driving factor of the underlying conduct, imposing even a $150 fee can prolong someone’s court involvement and compound their hardship, keeping them off the path to stability or recovery. In other cases, defense attorneys may file motions to waive such fees and prosecutors may agree or recommend to the judge that the fees be waived.

Finally, as we have said before, completing community service within the requisite timeframe may mean people need to call out of or cancel work, miss classes, or arrange childcare. Though many judges allow individuals to do community service at a place of their choice, some mandate that individuals serve through the state-run program that requires manual labor and is only offered on certain days.

It’s important to note that this kind of community service has no restorative value and is imposed before a person has been convicted of any wrongdoing. Pre-arraignment community service is simply a punishment for being arrested.

We also note that, though DA Rollins emphasized during her campaign the need to get people access to services, not hand down sentences, we often see punitive conditions (court costs and community service hours) to address what DA Rollins has identified as root causes in many cases like these: poverty, addiction, and mental illness. Especially in theft cases, where poverty or addiction may be a primary driving factor of the underlying conduct, imposing even a $150 fee can prolong someone’s court involvement and compound their hardship, keeping them off the path to stability or recovery. In other cases, defense attorneys may file motions to waive such fees and prosecutors may agree or recommend to the judge that the fees be waived.

Finally, as we have said before, completing community service within the requisite timeframe may mean people need to call out of or cancel work, miss classes, or arrange childcare. Though many judges allow individuals to do community service at a place of their choice, some mandate that individuals serve through the state-run program that requires manual labor and is only offered on certain days.

It’s important to note that this kind of community service has no restorative value and is imposed before a person has been convicted of any wrongdoing. Pre-arraignment community service is simply a punishment for being arrested.

Release or Detention Decisions

In 17 cases that advanced as criminal matters, the person being arraigned was released on personal recognizance. In many such cases, the court also imposed conditions—especially common was a stay away or no contact order for the place of the incident or a person involved. Sometimes a person is required to stay away from their own home or a major transit hub through which they have to commute.

In 4 cases exclusively involving charges DA Rollins pledged to decline this week, bail was set. Bail amounts ranged from $100 to $400. In 2 of these 4 cases, the individual being arraigned was facing charges of drug possession and/or possession with intent to distribute. We’ve seen repeatedly that the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office continues to treat drug charges like these as a serious crime, even though they are among the charges to be declined.

In the remaining 17 cases, we don’t know the final release decision or case outcome because the arraignment was continued—i.e. postponed to a future date or time (5 cases), the person being arraigned remained detained (despite the judge deciding to release them on personal recognizance on the pending charges) in order to resolve a warrant in another court (1 case), the person did not appear for arraignment and a warrant was issued (8 cases), the person had their bail revoked on a prior case and was held for transport to another court (1 case), or the courtwatcher wasn’t sure what happened (2 cases).

We note that people not showing up for arraignment happens rarely, and that courts don’t have to verify that a person actually received a summons before issuing an arrest warrant—a disturbing practice we hope DA Rollins will push to change. Our observed non-appearance rate among these minor charges was 8 cases out of 90, a rate of just 8.9%.

Our data collection on bail may undercount people who have already paid bail at the police station. Courtwatchers have not always been able to reliably document when someone has already posted bail, and in what amount, if they freely walk into court. This is not always explicitly addressed on the record.

Bail is set at the police station by court clerks. How bail amounts are decided is not transparent to the public and bail is set with very little oversight.

In two of the cases this week in which bail was set at arraignment, the judge simply reaffirmed what the bail magistrate had already imposed, which the person had already posted.

In 4 cases exclusively involving charges DA Rollins pledged to decline this week, bail was set. Bail amounts ranged from $100 to $400. In 2 of these 4 cases, the individual being arraigned was facing charges of drug possession and/or possession with intent to distribute. We’ve seen repeatedly that the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office continues to treat drug charges like these as a serious crime, even though they are among the charges to be declined.

In the remaining 17 cases, we don’t know the final release decision or case outcome because the arraignment was continued—i.e. postponed to a future date or time (5 cases), the person being arraigned remained detained (despite the judge deciding to release them on personal recognizance on the pending charges) in order to resolve a warrant in another court (1 case), the person did not appear for arraignment and a warrant was issued (8 cases), the person had their bail revoked on a prior case and was held for transport to another court (1 case), or the courtwatcher wasn’t sure what happened (2 cases).

We note that people not showing up for arraignment happens rarely, and that courts don’t have to verify that a person actually received a summons before issuing an arrest warrant—a disturbing practice we hope DA Rollins will push to change. Our observed non-appearance rate among these minor charges was 8 cases out of 90, a rate of just 8.9%.

Our data collection on bail may undercount people who have already paid bail at the police station. Courtwatchers have not always been able to reliably document when someone has already posted bail, and in what amount, if they freely walk into court. This is not always explicitly addressed on the record.

Bail is set at the police station by court clerks. How bail amounts are decided is not transparent to the public and bail is set with very little oversight.

In two of the cases this week in which bail was set at arraignment, the judge simply reaffirmed what the bail magistrate had already imposed, which the person had already posted.

The charge breakdowns are as follows [keep in mind that some folks had multiple charges]:

|

Charge

|

Number of Cases

Week 6 |

Total So Far

All 6 Weeks |

|

Trespass

|

15

|

53

|

|

Shoplifting

|

4

|

23

|

|

Larceny under $1200

|

3

|

26

|

|

Disorderly Conduct

|

5

|

17

|

|

Disturbing the Peace

|

(zero)

|

2

|

|

Receiving Stolen Property

|

1

|

10

|

|

Driving Cases (suspended or revoked license or registration)

|

41

|

283

|

|

Breaking and entering for the purpose of shelter

|

(zero)

|

2

|

|

Wanton/Malicious Destruction of Property

|

3

|

10

|

|

Threats (not domestic violence related)

|

3

|

16

|

|

Minor in Possession of Alcohol

|

(zero)

|

(zero)

|

|

Drug Possession

|

15

|

74

|